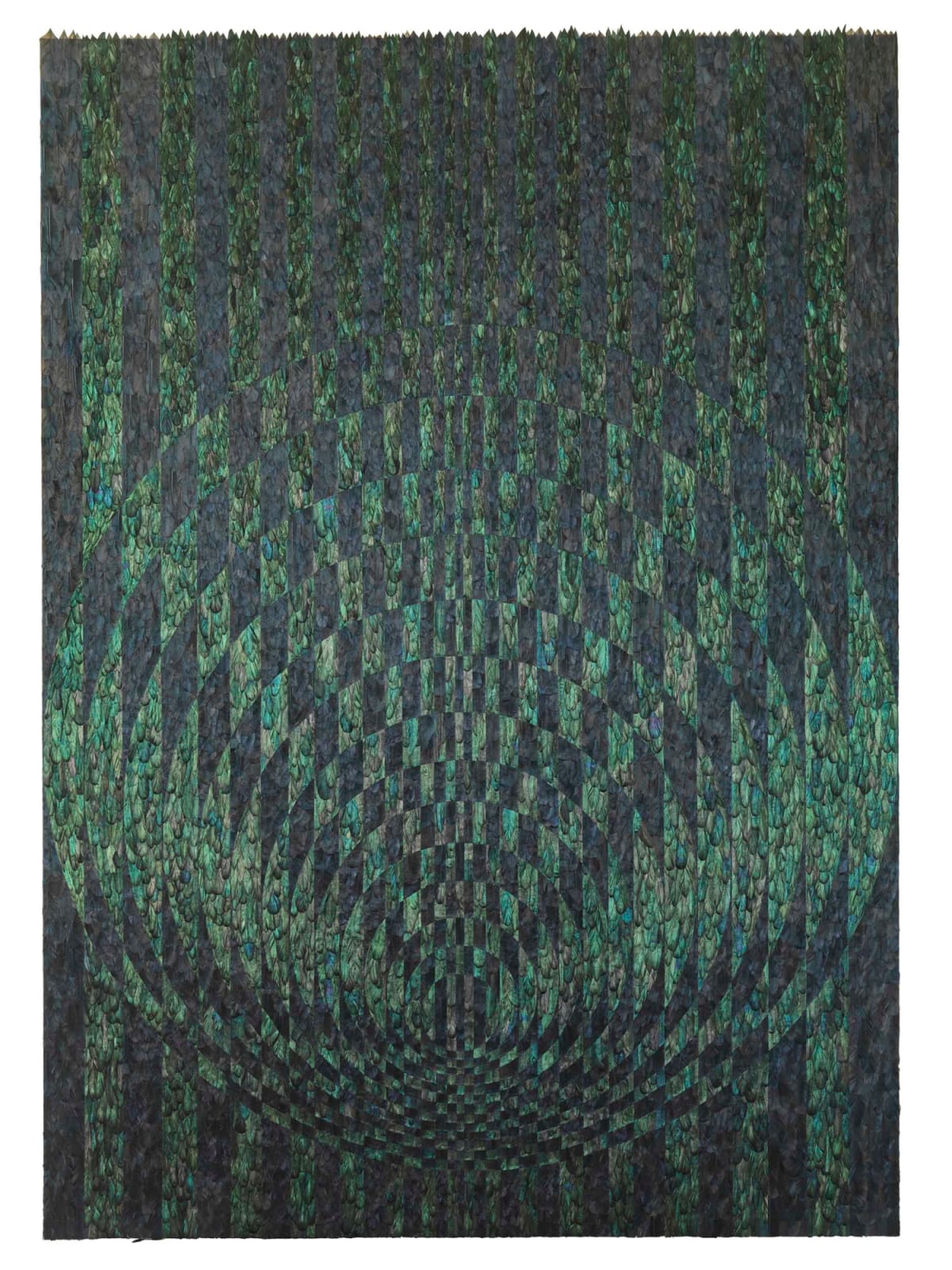

George Taylor British, b. 1975

The Beast In Me, 2017

Cockerel and crow feathers

231 x 170 x 8.5 cm (Framed)

91 x 66 7/8 x 3 3/8 in

91 x 66 7/8 x 3 3/8 in

Unique

'The Beast In Me' is one of George Taylor's largest and most ambitious works to date. This sumptuous wall relief, intricately made by hand using iridescent cockerel and crow feathers,...

'The Beast In Me' is one of George Taylor's largest and most ambitious works to date. This sumptuous wall relief, intricately made by hand using iridescent cockerel and crow feathers, is inspired both by the writer Baudelaire in its making process and Bridget Riley in its reference to Op Art.

Born in Macclesfield in 1975, George Taylor moved at the age of 10 onto the farm set within its own steep-sided secluded valley in a remote part of Gloucestershire. Here she began working with her father as he tended livestock and managed the woodland, initiating what has been a lifelong enchantment with the natural world especially as a creative environment beyond landscape solely as a leisure destination – more as a site from to engage with contemporary issues such as embodied experience in place.

At Bretton Hall, University of Leeds, she experimented with sculptural form and constructed environments, introduced by tutor John Penny to the work of Minimalism and Land artists such as Walter de Maria. Indeed the latter’s ‘Lightning Field’, 1977, prompted her to install six 30-foot steel poles in the small lake in the valley. Yet her urge to form a new creative language, as she says “Donald Judd meets Meret Oppenheim”, which could speak of the daily reality of life and death in farming, particularly at lambing and calving time, drove her to work with the residual materials of living forms, animal skins such as goat or snake, then ultimately feathers.

Her current body of work emerged in 2013 from a little sculptural sketch that she felt compelled to make on re-reading Georges Bataille’s ‘The Story of the Eye’, where she glued five blown quail’s eggs, originally destined for lunch, to an old satellite dish in a perfunctory yet deliberate hexagonal pattern. As she scaled up the pattern onto four foot discs, the relation between the intricate complexity of each egg’s surface and its bare pale interior sparked in her mind a passage from Luce Irigary’s text ‘Elemental Passions’ that refers to the open exchange of the kiss, ‘But when lips kiss, openness is not the opposite of closure. Closed lips remain open. And their touching allows movement from inside to outside, from outside to in, with no fastening nor opening of the mouth to stop the exchange.’ The lips are as a moebius strip where inside and outside surface combine, interchange and replace one another in an erotic dance that evokes the play of presence and absence of life and death. Taylor then embarked on the gesture of ‘softening the hard-edges of Minimalism’ by taking seminal Bridget Riley Op Art compositions that suggest this open folding in and out, overlaying the graphic design with the variegated hues and exotic texture of feathers, as both homage and gauntlet.

George Taylor's current body of work emerged in 2013 from a little sculptural sketch that she felt compelled to make on re-reading Georges Bataille’s ‘The Story of the Eye’, where she glued five blown quail’s eggs, originally destined for lunch, to an old satellite dish in a perfunctory yet deliberate hexagonal pattern.

As she scaled up the pattern onto four foot discs, the relation between the intricate complexity of each egg’s surface and its bare pale interior sparked in her mind a passage from Luce Irigary’s text ‘Elemental Passions’ that refers to the open exchange of the kiss, ‘But when lips kiss, openness is not the opposite of closure. Closed lips remain open. And their touching allows movement from inside to outside, from outside to in, with no fastening nor opening of the mouth to stop the exchange.’ The lips are as a moebius strip where inside and outside surface combine, interchange and replace one another in an erotic dance that evokes the play of presence and absence of life and death.

Taylor then embarked on the gesture of ‘softening the hard-edges of Minimalism’ by taking seminal Bridget Riley Op Art compositions that suggest this open folding in and out, overlaying the graphic design with the variegated hues and exotic texture of feathers, as both homage and gauntlet. 'The Beast In Me' is one of the largest works from this series and uses carefully sourced cockerel and raven feathers to make an exquisite optical pattern that has an extraordinary depth of colour and sensuality.

Her studies culminated in 1998, with the creation of total immersive environments where the viewer was oriented in a single direction through feather-lined passages connotative of our passage through life, articulating her interest in Gaston Bachelard’s metaphorical evocation of the links between phenomenological architectural spaces and the nuomenal world sensed from within our body and memory, succinctly captured by his phrase ‘intimate immensity’. Work following College saw Taylor continuing her exploration into expanded possibilities for sculptural form and environments as art assistant in the studios of Dan Chadwick and Science Ltd, and in the Fashion Industry, strategically applying herself to the role of the ‘motivating object’, the subject of what Film theorist Laura Mulvey has termed the ‘male gaze’ by working as model with the creative director, Isabella Blow.

Born in Macclesfield in 1975, George Taylor moved at the age of 10 onto the farm set within its own steep-sided secluded valley in a remote part of Gloucestershire. Here she began working with her father as he tended livestock and managed the woodland, initiating what has been a lifelong enchantment with the natural world especially as a creative environment beyond landscape solely as a leisure destination – more as a site from to engage with contemporary issues such as embodied experience in place.

At Bretton Hall, University of Leeds, she experimented with sculptural form and constructed environments, introduced by tutor John Penny to the work of Minimalism and Land artists such as Walter de Maria. Indeed the latter’s ‘Lightning Field’, 1977, prompted her to install six 30-foot steel poles in the small lake in the valley. Yet her urge to form a new creative language, as she says “Donald Judd meets Meret Oppenheim”, which could speak of the daily reality of life and death in farming, particularly at lambing and calving time, drove her to work with the residual materials of living forms, animal skins such as goat or snake, then ultimately feathers.

Her current body of work emerged in 2013 from a little sculptural sketch that she felt compelled to make on re-reading Georges Bataille’s ‘The Story of the Eye’, where she glued five blown quail’s eggs, originally destined for lunch, to an old satellite dish in a perfunctory yet deliberate hexagonal pattern. As she scaled up the pattern onto four foot discs, the relation between the intricate complexity of each egg’s surface and its bare pale interior sparked in her mind a passage from Luce Irigary’s text ‘Elemental Passions’ that refers to the open exchange of the kiss, ‘But when lips kiss, openness is not the opposite of closure. Closed lips remain open. And their touching allows movement from inside to outside, from outside to in, with no fastening nor opening of the mouth to stop the exchange.’ The lips are as a moebius strip where inside and outside surface combine, interchange and replace one another in an erotic dance that evokes the play of presence and absence of life and death. Taylor then embarked on the gesture of ‘softening the hard-edges of Minimalism’ by taking seminal Bridget Riley Op Art compositions that suggest this open folding in and out, overlaying the graphic design with the variegated hues and exotic texture of feathers, as both homage and gauntlet.

George Taylor's current body of work emerged in 2013 from a little sculptural sketch that she felt compelled to make on re-reading Georges Bataille’s ‘The Story of the Eye’, where she glued five blown quail’s eggs, originally destined for lunch, to an old satellite dish in a perfunctory yet deliberate hexagonal pattern.

As she scaled up the pattern onto four foot discs, the relation between the intricate complexity of each egg’s surface and its bare pale interior sparked in her mind a passage from Luce Irigary’s text ‘Elemental Passions’ that refers to the open exchange of the kiss, ‘But when lips kiss, openness is not the opposite of closure. Closed lips remain open. And their touching allows movement from inside to outside, from outside to in, with no fastening nor opening of the mouth to stop the exchange.’ The lips are as a moebius strip where inside and outside surface combine, interchange and replace one another in an erotic dance that evokes the play of presence and absence of life and death.

Taylor then embarked on the gesture of ‘softening the hard-edges of Minimalism’ by taking seminal Bridget Riley Op Art compositions that suggest this open folding in and out, overlaying the graphic design with the variegated hues and exotic texture of feathers, as both homage and gauntlet. 'The Beast In Me' is one of the largest works from this series and uses carefully sourced cockerel and raven feathers to make an exquisite optical pattern that has an extraordinary depth of colour and sensuality.

Her studies culminated in 1998, with the creation of total immersive environments where the viewer was oriented in a single direction through feather-lined passages connotative of our passage through life, articulating her interest in Gaston Bachelard’s metaphorical evocation of the links between phenomenological architectural spaces and the nuomenal world sensed from within our body and memory, succinctly captured by his phrase ‘intimate immensity’. Work following College saw Taylor continuing her exploration into expanded possibilities for sculptural form and environments as art assistant in the studios of Dan Chadwick and Science Ltd, and in the Fashion Industry, strategically applying herself to the role of the ‘motivating object’, the subject of what Film theorist Laura Mulvey has termed the ‘male gaze’ by working as model with the creative director, Isabella Blow.

Provenance

from the artist

Exhibitions

'Feathers, Bones & Stones', 2022, Pangolin London

George Taylor: Intimate Immensity, 2018,

Literature

George Taylor: Intimate Immensity, 2018, PL

Publications

George Taylor: Intimate Immensity, 2018, PL

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.