Whether it be physical or mental, artistic or architectural, culinary or couture, transformation is one of our most distinctive human traits. For me, an artist’s ability to transform basic materials into awe-inspiring objects is endlessly enthralling and since seeing Merete Rasmussen’s work at Canary Wharf for the first time in 2011, I have been fascinated by her ability to transform heavy, solid lumps of wet clay into dynamic, seemingly weightless, extraordinarily complex twists and loops. It requires enormous reserves of patience and resilience, endless hours of scraping and refining and an eye for precision as well as acute spatial awareness. Combined with Rasmussen’s intuitive flare for colour it is easy to see why Rasmussen’s works have been collected by major institutions and she has an impressive following of private collectors. Her work is not only technically brilliant but also a joy for the eyes.

Three years ago, Rasmussen and her family made the big decision to uproot and move out of London. Having shared a studio in Camberwell with two other talented ceramicists since ending her studies, she dreamt of building her own studio. Rasmussen and her husband settled on the gently undulating county of Sussex and found a dated bungalow ripe for improvement with a large garden, a plot for a studio and a stunning view out over a lush green valley. Balancing the challenges of settling her young daughter into a new school, DIY, architects plans, costings and re-costings, Rasmussen set up a makeshift studio in her shed at the bottom of the garden. Without a working kiln however she was forced to explore and experiment with alternative materials such as copper and wax.

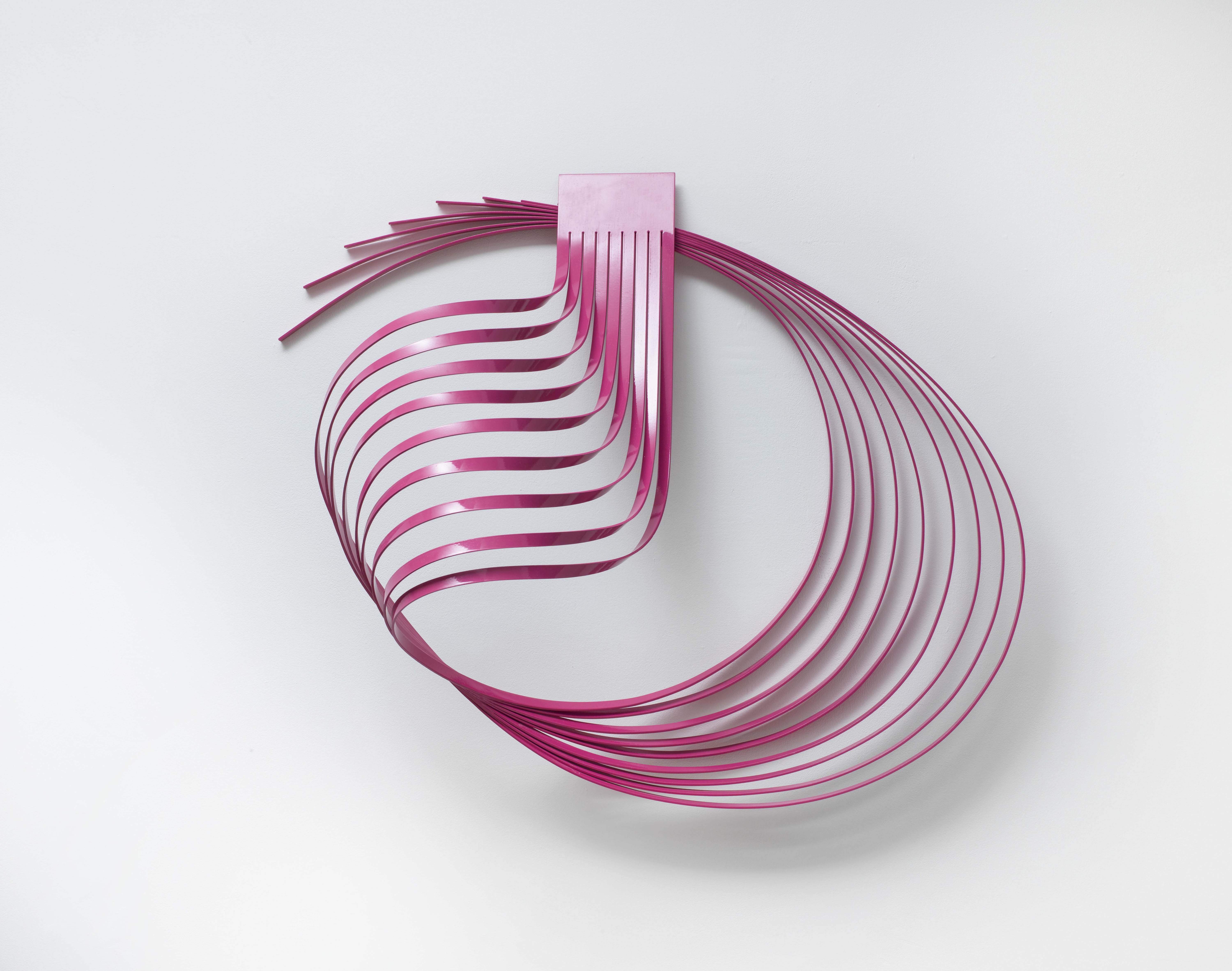

Progressing in confidence from the bronze works first shown in her last exhibition, Rasmussen has created works that are distinctly hers but explore each materials’ individual properties. Painted copper strips are precisely cut and manipulated to create complex forms such as the bright pink wall piece Multiple Form. Exquisite patinated or brushed bronzes and a polished silver have been cast directly from waxes, a material which she has only recently, yet skilfully, mastered. In these sculptures Rasmussen works the wax with gentle heat and hand to make unique objects that still bear the marks of her tools. Small and complex, these works would have been difficult to render in ceramic, and the quick, rough ceramic sketches that litter her studio highlight this but are an important part of the process for figuring out how she will build the larger works. Rasmussen has worked the same stoneware for over two decades and knows inside out its favoured assets and foibles, how it will take colour and how far she can push its tensile strength, however it is her flexibility in approach to material that has enabled her to work unencumbered by scale or lack of equipment.

As building works inevitably do, Rasmussen’s studio took longer to build than planned,

however a forced period out of the studio in this case seems to have been an inconvenient blessing. This exhibition is testament to a freshness of approach with Rasmussen relishing her return to a new, bright and airy studio, and creating an extraordinary body of new work that explores a number of new developments with a marked increase in confidence and maturity.

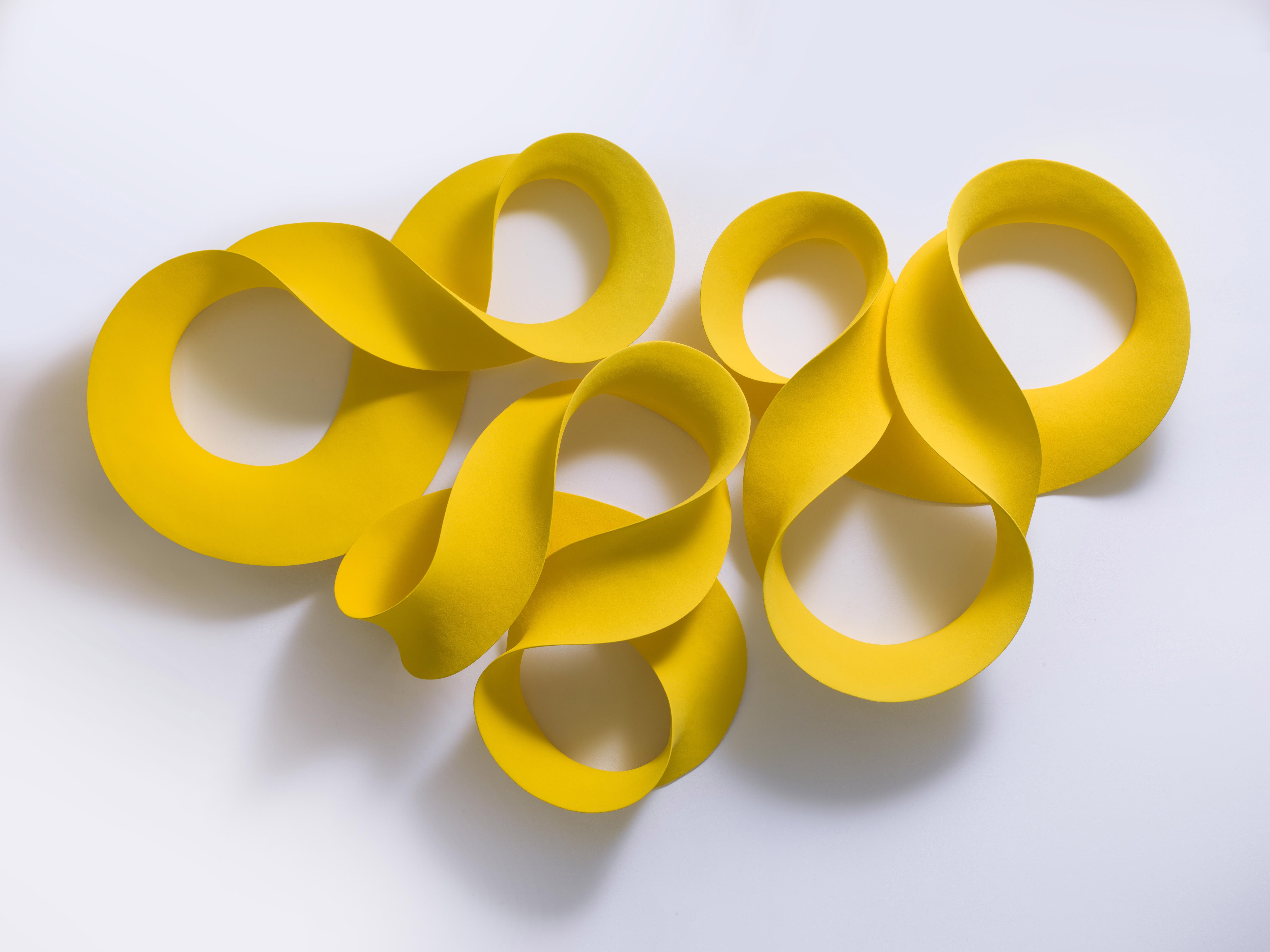

‘Ouroboros’, the Ancient Egyptian symbol of the serpent who bit his own tail which is used

in many cultures to illustrate birth and rebirth, is here referenced in an impressive three-part wall piece that cleverly expands across the wall so that the viewer can barely tell where one part ends and the next begins. Using a bright, matt yellow slip that seems to pulsate on the wall, Rasmussen’s expressive serpentine forms belie the time taken to slowly build each piece up using the equally snakelike coil technique.

Evolve is a breathtaking sculpture which Rasmussen designed to be as large as her kiln could manage and can be seen as a progression from her earlier monumental Morphogenesis (see pages 58-59). Exploring ideas of growth and the transition from uniform mathematical structures to organic, free-flowing forms, Evolve is a remarkable cuboid work that builds inwards from a regulated external carapace to an impulsive inner energy. This energy is emphasised by the fiery red to luminous orange graduated colour, a recent and exciting departure seen in a number of works in this exhibition along with the discovery of two new coloured slips seen in the works Impetus and Momentum.

Duality and the interaction between forms is also an interesting development in this new body of work with Fragments of Repeated Form and Dual Form exploring not only the negative space within the forms themselves but also the tensions between them. In Dual Form, the two vibrant orange forms nestle together to create a complex horizontal piece of impressive scale. In contrast, Fragments of Repeated Form with it’s matt black finish and similar interest in growth to Evolve, sits as two completely distinct elements that seem to reach out to communicate with each other in endless conversation, changing subtly depending on the two parts arrangement.

This exhibition signals a new chapter in Rasmussen’s work. The riot of colour and the complexity of form are instantly recognisable but there is a new sense of seriousness, of challenge and progression perhaps felt more fervently after a short break to think and regroup. Rasmussen’s work is an ongoing and exciting transformation and whilst transformation may be part of human DNA there are only a few who can succeed in pushing it beyond its limits and to a higher level. In this age where many of us assume such transformation must require an element of digital assistance it is refreshing that this exhibition relishes purely the hand-made: transforming mud to majesty and wax to wonder.