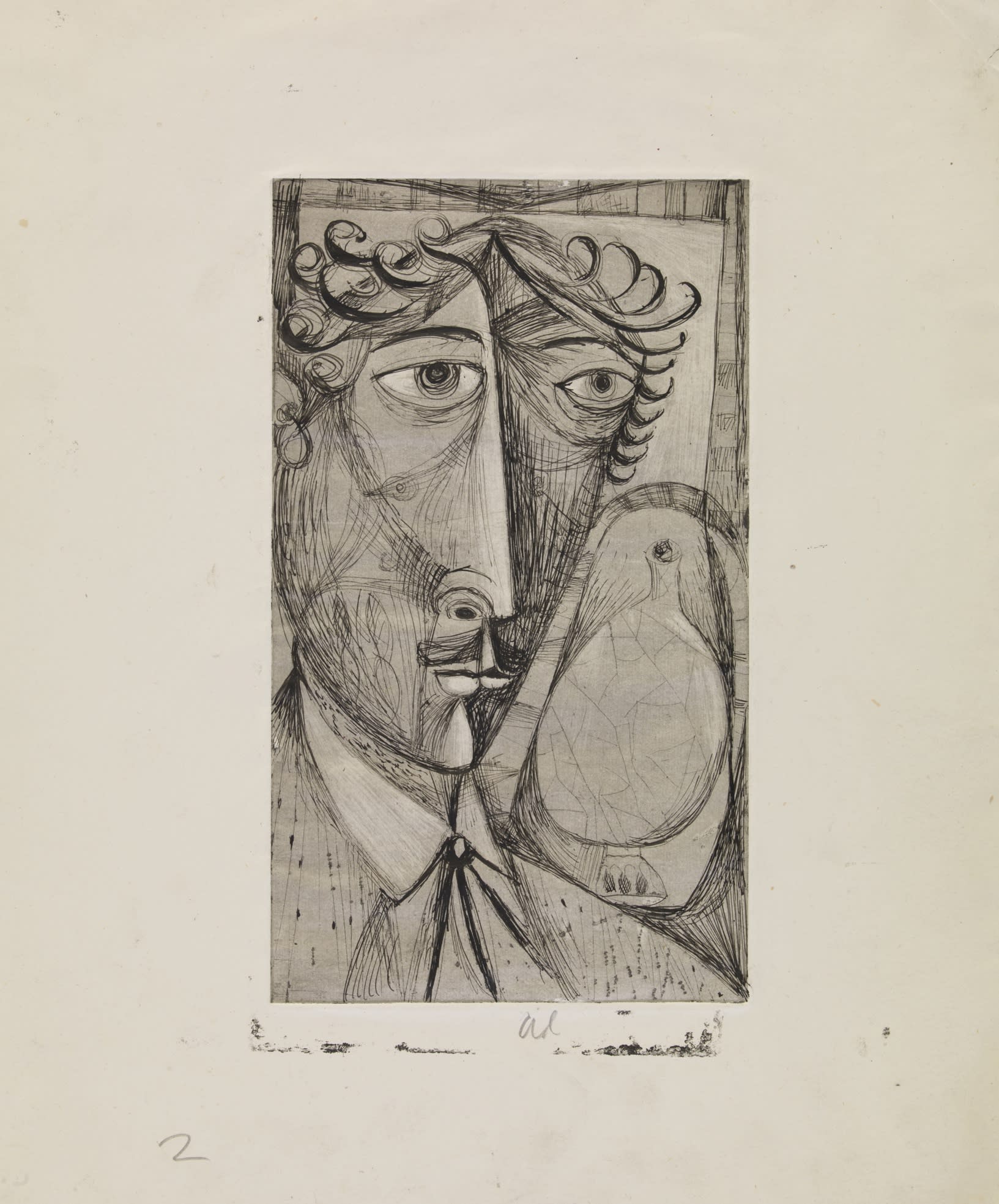

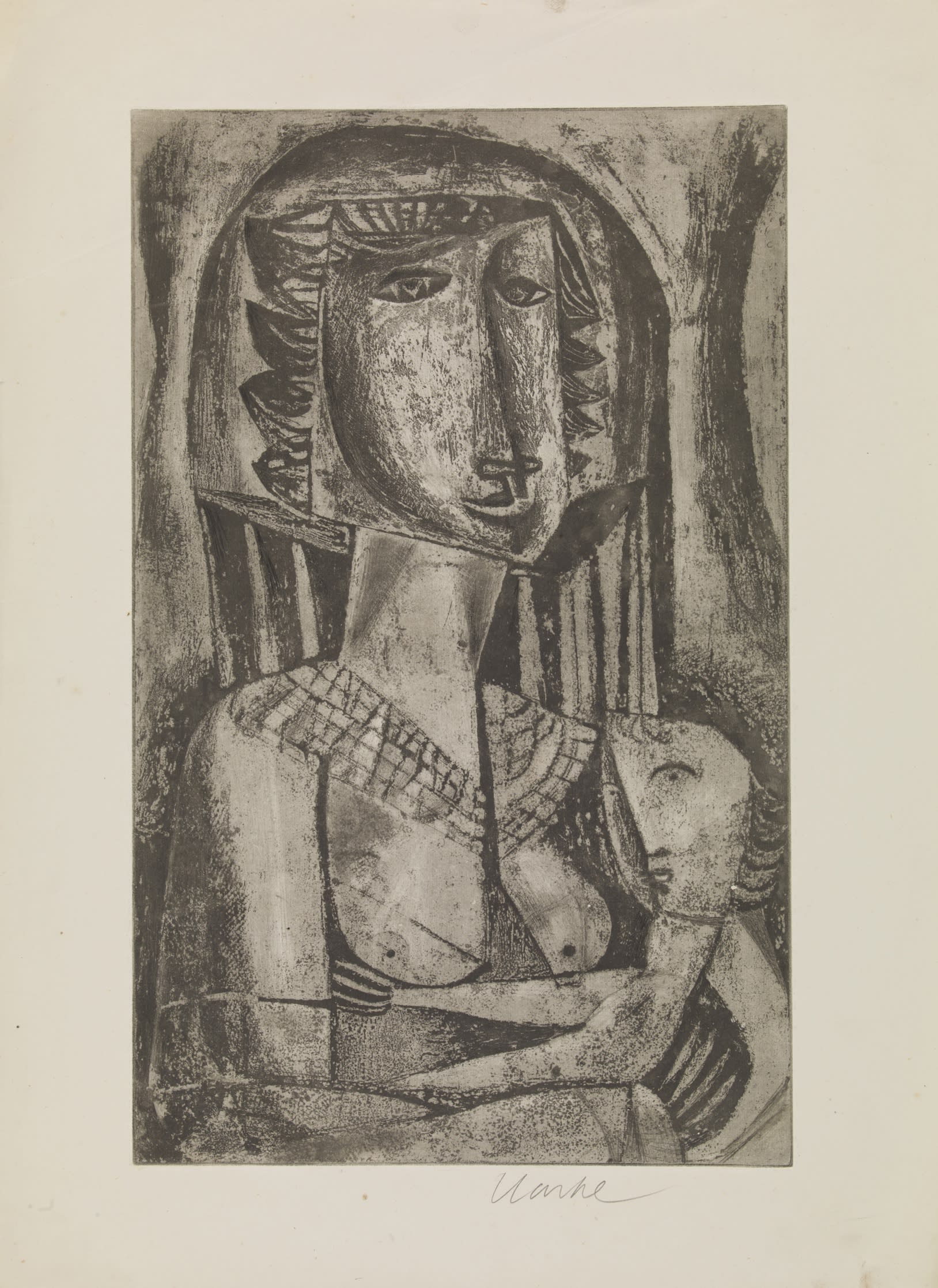

Let's start with two early prints. A Self Portrait (1949), made when Geoffrey was probably twenty-four, shows him looking serious. He's dressed in a tightly buttoned collar and tie, with a neat moustache, exaggeratedly long nose, and curly hair fanning around his head. Next, in Mother and Child (1949), we see again the long face, eyes near the top, but the eyes aren't level, and there is a definite curve to the face. These are ideas Geoffrey borrowed from Modigliani, but there is also the influence of Cubism and Byzantine icons. It's a melting-pot of styles and ideas, typical of a student's thirst for knowledge.

From these early prints, I'll now rewind, to trace how Geoffrey reached this point.

Geoffrey Clarke, Self Portrait, 1949, Proofed in three states.

Geoffrey Clarke, Mother and Child, 1949, Edition of 20.

Geoffrey was born in 1924 in Derbyshire. His father was an architect, who took him on his sketching expeditions to draw landscapes, which he later made into etchings. Geoffrey's grandfather, a church furnisher, visited parishes with sample books of stained glass and ecclesiastical fittings. Early on, Geoffrey could make beautiful line drawings of buildings in perspective, and aged sixteen he went to art school. In 1943 he was conscripted into the RAF, following which he enrolled at the Lancaster and Morecambe School of Arts and Crafts, which had a reputation as a springboard to the Royal College of Art.

Geoffrey's teacher at Lancaster was the painter, potter and stained-glass artist Ronald Grimshaw, who was exactly what Geoffrey needed: a maverick. Grimshaw read poetry in his classes, but he knew all about modernism, and encouraged students to use any method - even their feet - to get the effects they wanted. He was the first to discuss symbolism with Geoffrey, and remained a crucial influence throughout his life. Vital, too, was the place where Geoffrey lodged, Warton vicarage, and his friendship with Rev Eric Rothwell. This period was, effectively, his spiritual awakening - a dawning of the interconnectedness of nature, landscape and existence.

Gaining a place at the RCA, in Graphic Design, Geoffrey quickly shifted to Stained Glass. At the beginning of his second term, in January 1949, he borrowed his father's small etching press and started printmaking in the attic room of his lodgings. What happened next - ironically - is that Geoffrey got flu. And while lying there in the autumn of 1949, feverish, then exhausted, he completely rethought his artistic language. He started with pencil sketches, which he filed, carefully, in a manila folder inscribed 'Within this folder lies a new world'.

This new world was peopled with spindly figures, their eyes on external branches, engaged in preaching, juggling, tending sheep. Trees became arrows - like a child's drawing of a Christmas tree - and everywhere was the symbol of the cross, uniting man with landscape. When Geoffrey started etching again, in January 1950, his work was transformed. There was no sense of volume, but instead a linear world - a landscape of the imagination. A tiny Shepherd has two stocky legs, a triangular 'skirt', and two arms raised to clutch a cross. In Man 'Concealed' Behind Trees (1950), the depiction is even more abstract. The figure again holds a cross but stands on a table, and something strange descends from the sky - like a bristling wand.

This takes us neatly to the exhibition's title, 'Intuitionism'. For Geoffrey's diploma he was required to write a thesis. He didn't like writing, but approached the task with characteristic seriousness. First he divided his thesis in two. One half contained a précis of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, which he saw as parallel to his own spiritual quest, but the other, 'Exposition of a Belief', became his artistic creed. In it he defined his belief in abstraction and the spiritual foundation of art, and introduced the symbols in his work: the chalice, the cross, the unity of man, nature and the supreme spiritual force - he didn't name it as God, just as he rarely named his belief, explicitly, as Christian. A table represents earth, the bristling wand (also a circle, sun or raincloud) is the divine presence. And here we enter the cycle of intuitionism, as it becomes apparent that Geoffrey's whole world is a balancing act. Intellect balances intuition.

In Geoffrey's depictions of man, there is often an external divine presence, as well as a cross within the figure's head, with the idea that these inner and outer forces must be unified to reach spiritual equilibrium. Adoration of Nature (1951) exemplifies this balance. Two figures, man and woman, are planted on the earth (a table), through which a tree - representing nature - grows. Above is a sun or raincloud, blessing and sustaining the tree. And actually, if we look at the figures' arms, reaching towards the precious tree, they might be the arms of the child, reaching towards its mother, in the earlier Mother and Child.

Geoffrey Clarke, Adoration of Nature, 1951, Edition of 10.

Geoffrey's thesis, completed in 1951, is a stunning object: leather-bound, with an iron relief set into the cover, and containing actual prints of etchings in this exhibition. If he felt nervous about writing the text itself, the idea was to 'knock 'em dead' with the presentation. He was awarded a gold medal when he finally completed his studies.

But meanwhile, Geoffrey was already exhibiting. He was commissioned to makea large iron and glass sculpture, Icarus, for the Festival of Britain. Adoration of Nature was commissioned by the designer Robin Day, to feature on a piece of furniture which was part of a prize-winning installation at the Milan Triennale. Geoffrey's iron sculpture was included in the 1952 Venice Biennale, the first international showing of a young, ambitious generation that included Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick and Eduardo Paolozzi. And from that point, his career took off. Geoffrey was commissioned to make stained glass for the new Coventry Cathedral, and took part in a succession of prestigious architectural projects which occupied him until the later 1960s. For that reason, he rarely found time for printmaking.

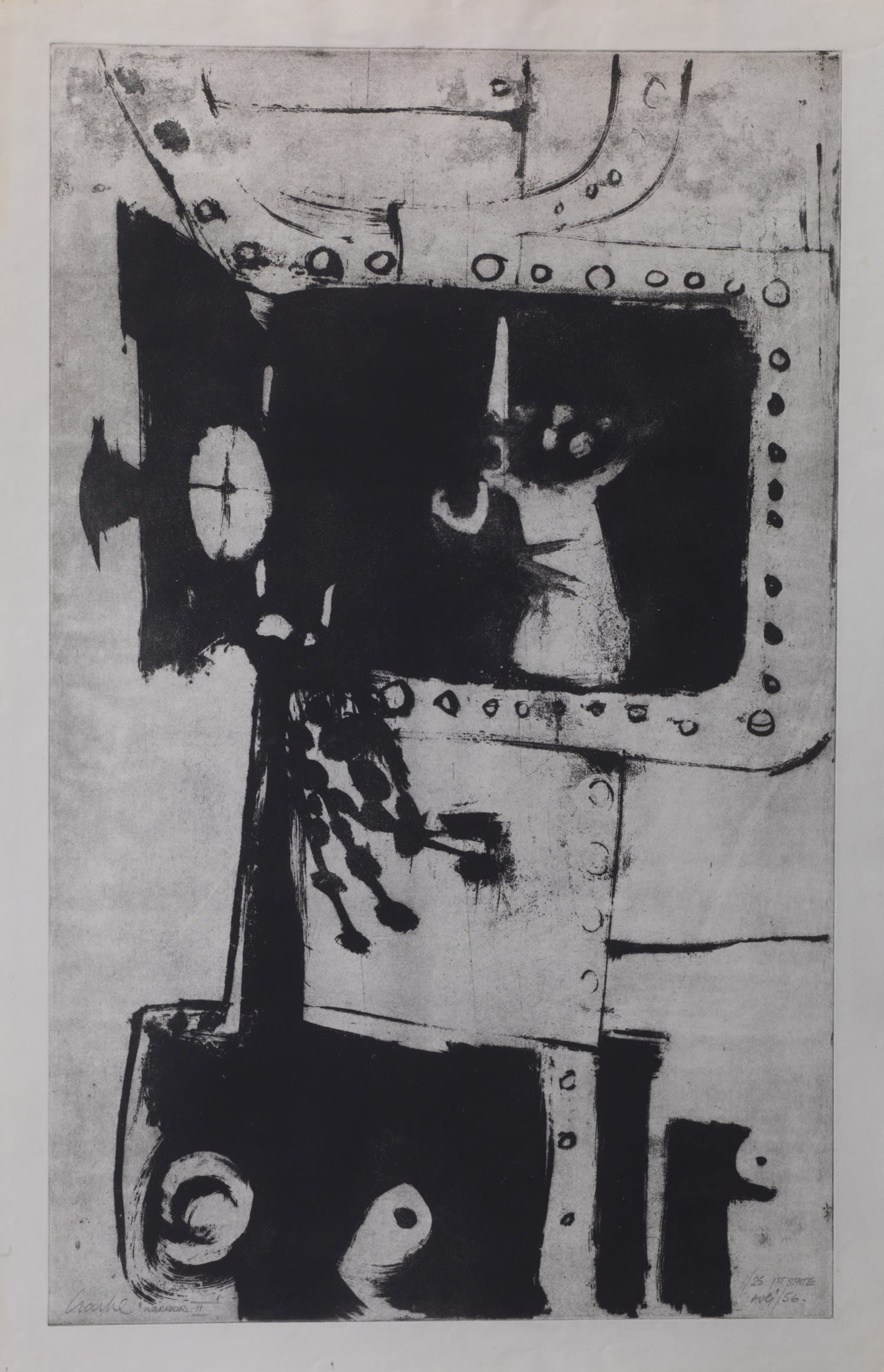

Within his work, however, there remained two constants: symbolism and a fascination with materials. Geoffrey wrote in his thesis that 'there are many images for man'. This was before sensitivity about language, so when Geoffrey said 'man', he meant humankind, man and woman. His prints indeed include many symbols for man, but once your eye becomes accustomed, you can decode what's happening. There are families, single figures, warriors, footballers and a harlequin - taking in a dizzying array of forms. In the mid-1980s, Geoffrey revisited this imagery and developed it in cast aluminium. An etched Warrior II (1956), peering from his helmet, thus became an aluminium Tankman (1984), half-concealed within an observation hatch. Likewise, the figures in Adoration of Nature became the chunkier man and woman of Towards a Constant.

Geoffrey Clarke, Warrior II, 1956, Edition of 25.

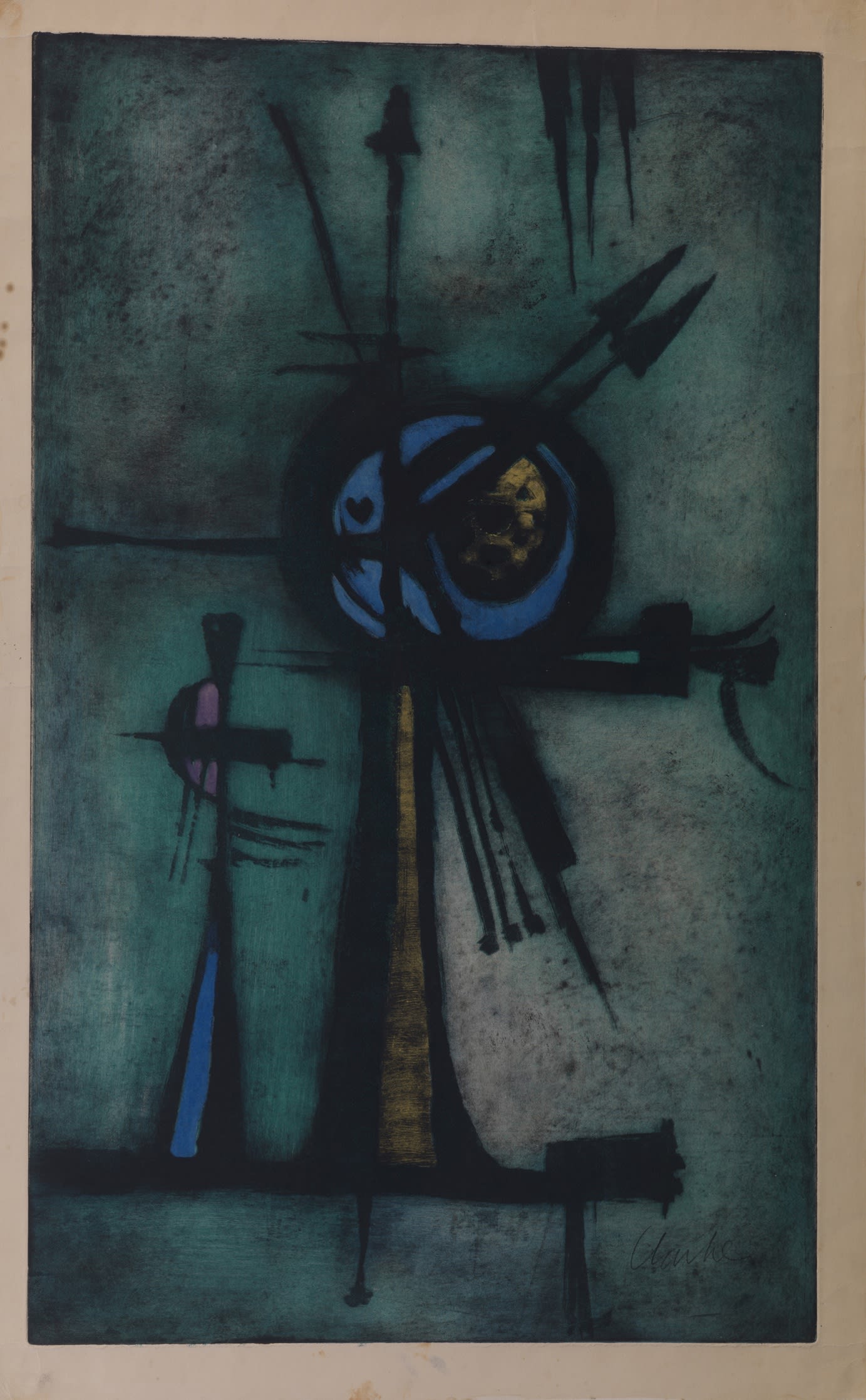

Then we have materials. Although there is a development in Geoffrey's use of techniques, there is also a creative wilfulness in his disregard for tradition. Starting with copper plates, he progressed to steel, which add texture without the use of aquatint grounds. Looking at Picasso's prints he became interested in sugar-lift. You can see this in etchings with a strong black line, which originates from painting sugar solution onto the plate with a brush. Geoffrey printed smaller etchings on his father's portable press and larger ones at the RCA. The warriors, from 1956, were taken to Paris, to be printed by Picasso's printer, Jacques Frélaut - a trip sponsored by Robert Erskine, who owned St George's Gallery and commissioned the colour version of Harlequin (1956).

But because Geoffrey enjoyed printmaking, he preferred to do it himself. Printing can be a very individual process, by varying the viscosity of the ink, the intensity of the colour, and by wiping the plate to leave thinner or thicker patches of ink. If a professional printer makes an edition, the aim is to make every print identical. But for Geoffrey each print presented a new opportunity, which could drive dealers and collectors mad. Frequently he didn't complete editions. Sometimes, later on, dealers commissioned new editions - with Geoffrey's authorisation. Comparing the two, the prints Geoffrey made are usually on thinner paper, and often have a dark, stormy quality to the inking.

This exhibition highlights printmaking, yet it also demonstrates the breadth of Geoffrey's work, crossing into design, sculpture, glass, jewellery and furnishings. There are sketches for textiles, a wallpaper sample and wonderful iron sculptures, which relate to the etchings, as well as etchings, such as Study for Sculpture (1956), which relate to stained glass. Aluminium sculptures show the casting technique he developed at his studio in Suffolk. We can also see how Geoffrey dreamed - in the tiny maquettes and plateaus which were envisaged on an environmental scale, and the exquisite jewellery, sculptures to be worn. But it all began with the etchings, and it's through these, really, that we can make sense of a life's work.

Geoffrey Clarke, Study of Sculpture, 1956, Edition of 30.

JUDITH LEGROVE

To see a film of the 'Geoffrey Clarke: Intuitionism' exhibition click here