WELCOME TO OUR SCULPTURE BLOG!

AS THE UK'S LEADING SCULPTURE GALLERY, OUR BLOG WILL BRING YOU INSIGHTFUL ARTICLES, INTERVIEWS AND COMMENTS ON OUR FAVOURITE SUBJECT - SCULPTURE!

If you would like to see a selection of available works to purchase by any of the artists mentioned throughout the blog, please contact the gallery via email on: gallery@pangolinlondon.com or call 020 7520 1480.

Our friendly team are happy to help.

-

In Conversation with Bryan Kneale

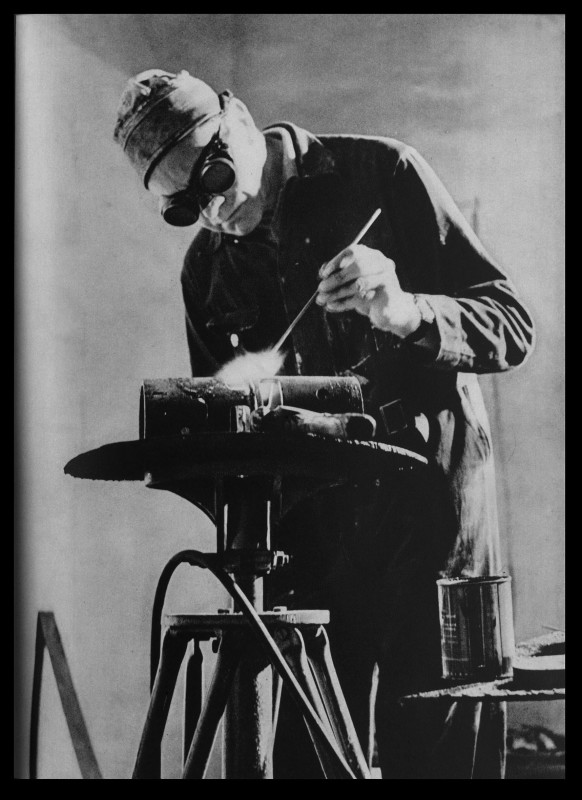

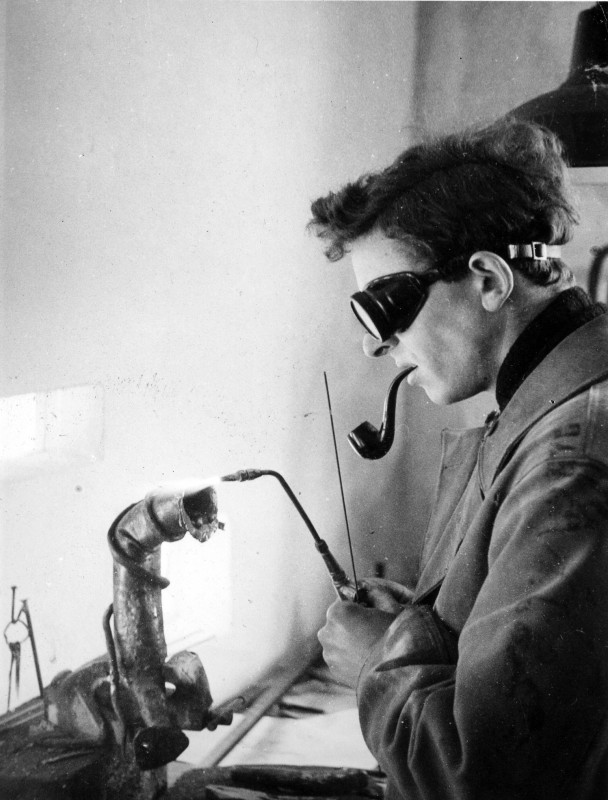

Included in the catalogue 'Bryan Kneale: Through the Ellipse' This interview was conducted to co-incide with Pangolin London's 2022 exhibition, 'Bryan Kneale:Through the Ellipse', and is included in the catalogue. Learn more about the exhibition here, and purchase the catalogue here.Algernon Mitchell: You’ve been making art for over five decades now. I’m interested to hear your perspective on how the art world has changed since you were starting out.Bryan Kneale: It has changed enormously. The possibilities for a young artist in my lifetime were more or less non-existent, except for one or two things. There were hardly any galleries in London which were willing to show young artists, and I was incredibly lucky - partly through my own arrogance as a student in deciding what I wanted to do and announcing to all and sundry that it was time I put myself under the public gaze. I was lucky enough to force myself on the Redfern Gallery, who were very encouraging. I showed them one or two thingsI’d done, and they said to me, ‘Well, if you could show us a couple of hundred paintings that you’ve been doing over the years...’ Which, of course, didn’t exist. So, I then shut myself away and produced a hundred paintings, and luckily I was able to survive on a small allowance from my father. And when I’d made my paintings, I went to the gallery and of course, they’d totally forgotten me. I’d lived this crazy dream of going in and showing my work to them, and then I found that reality had struck, and there I was with my paintings... But, to my enormous relief, they decided to give me my first exhibition. I owe the beginnings of my career to luck and, I suppose, self-belief. I was very lucky to have found a sympathetic gallery in the Redfern.AM: Jumping ahead to the present day, how would you say your practice has changed in the last ten years?BK: The main thing is that I had a massive stroke in 2014, which rendered my body, to some extent, paralysed, and so I am now dependant on working and living in a wheelchair. But other artists have managed.AM: Matisse, for example.BK: Yes. Lots of people have managed, but it makes things a bit difficult at times. I’ve been lucky enough to have a good studio and I’m able to work from home, straight across the garden into the studio. Particularly in my paintings, I make use of a painting knife, which means I can manipulate directly onto the surface with my good arm. The stroke did mean the end of my physical ability to weld or cut metal, or use machines, so I’ve found other ways, and other people to work with.AM: I’ve noticed a lot of tools and materials in your studio that I’d normally associate with making scale models – you have a desktop vacuum former, texture pastes, and you’re painting on styrene sheets.BK: The reason I’m using styrene is because I wanted to have a perfectly smooth surface to work on, which would allow me to manipulate my painting knives.

This interview was conducted to co-incide with Pangolin London's 2022 exhibition, 'Bryan Kneale:Through the Ellipse', and is included in the catalogue. Learn more about the exhibition here, and purchase the catalogue here.Algernon Mitchell: You’ve been making art for over five decades now. I’m interested to hear your perspective on how the art world has changed since you were starting out.Bryan Kneale: It has changed enormously. The possibilities for a young artist in my lifetime were more or less non-existent, except for one or two things. There were hardly any galleries in London which were willing to show young artists, and I was incredibly lucky - partly through my own arrogance as a student in deciding what I wanted to do and announcing to all and sundry that it was time I put myself under the public gaze. I was lucky enough to force myself on the Redfern Gallery, who were very encouraging. I showed them one or two thingsI’d done, and they said to me, ‘Well, if you could show us a couple of hundred paintings that you’ve been doing over the years...’ Which, of course, didn’t exist. So, I then shut myself away and produced a hundred paintings, and luckily I was able to survive on a small allowance from my father. And when I’d made my paintings, I went to the gallery and of course, they’d totally forgotten me. I’d lived this crazy dream of going in and showing my work to them, and then I found that reality had struck, and there I was with my paintings... But, to my enormous relief, they decided to give me my first exhibition. I owe the beginnings of my career to luck and, I suppose, self-belief. I was very lucky to have found a sympathetic gallery in the Redfern.AM: Jumping ahead to the present day, how would you say your practice has changed in the last ten years?BK: The main thing is that I had a massive stroke in 2014, which rendered my body, to some extent, paralysed, and so I am now dependant on working and living in a wheelchair. But other artists have managed.AM: Matisse, for example.BK: Yes. Lots of people have managed, but it makes things a bit difficult at times. I’ve been lucky enough to have a good studio and I’m able to work from home, straight across the garden into the studio. Particularly in my paintings, I make use of a painting knife, which means I can manipulate directly onto the surface with my good arm. The stroke did mean the end of my physical ability to weld or cut metal, or use machines, so I’ve found other ways, and other people to work with.AM: I’ve noticed a lot of tools and materials in your studio that I’d normally associate with making scale models – you have a desktop vacuum former, texture pastes, and you’re painting on styrene sheets.BK: The reason I’m using styrene is because I wanted to have a perfectly smooth surface to work on, which would allow me to manipulate my painting knives.

It started with the idea of working on canvas, to bring the canvas surface to an immaculate smooth surface, and then I thought, ‘Well, why don’t I use something which has got that quality anyway?’ So that brought me round to using styrene, which of course I had used in model making for quite a long time. Small models for large sculptures were usually made with bits of plastic and styrene.AM: There is an enormous tonal variety between the paintings as well. What kind of decision-making process informs the choice of colour, if any?BK: It’s just whatever comes out of the tube that I use. The colour does come into it – not so much as the colour itself, but as a single means of creating form.AM: So based on what you’ve said, whilst they are clearly separate, do you see the painting and the sculpture as having an intrinsic link?BK: Yes, I think the paintings are obviously much more instantaneous. Because I use form in the paintings, they are, in fact, three-dimensional. There’s one particular piece, which I called Miracle, which is where I finally broke through to make a three-dimensional and lively piece, which I was lucky enough to be able to manage. Because I can still paint, though I can’t sculpt. To make things by manipulating machines like I used – it’s out of the question.AM: The new sculptures obviously also have this large elliptical void in them, which inspired the title of the show. That’s a form I’ve noticed in some of your other sculptures, and it also shows up in some of the paintings as well. I was wondering if you could tell me about what your interest in that void space is – if that’s the right way to even characterise it?BK: Well, I’ve thought about this quite a bit. It sounds rather melancholic, which is not surprising when you’re 92, to have some thoughts of a melancholic nature, especially when one’s friends seem to be departing this world in an ever- increasing number. One of the things I’ve never forgotten is in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, which of course holds the graves of many famous artists, like Delacroix, Oscar Wilde, all sorts. At the end of the cemetery is a thing like a wall, with a large void space in the centre, which a series of figures, men and women, are moving endlessly toward, which of course is the end of life. I thought it was very affecting, and very memorable, so to some extent, I suppose, so too are these things I’ve made myself, they resonate for me with that piece. It sounds rather pretentious, but it’s probably true. I think this series of works will probably be my finale, whereas in the past, all of my sculptures led on, one endlessly into another. They’re mostly about how forms interact with each other, how shapes can be conceived and constructed, so that they have a life of their own.AM: You mentioned the last time that I was here that you saw these pieces as the culmination of your practice. Is this what you meant when you said that?BK: Yes, yes, I think so. Obviously, being confined to a wheelchair has affected me considerably, being in my earlier days a very physical sort of chap, who was always half-blacksmith, half-sculptor. I remember something a critic once said about my work, that I had become like one of those things which are half-horse, half-man.AM: A centaur?BK: Yes. He said I had turned into a centaur: half-man, half-metal. And I thought that was the nicest thing anyone had ever said about me! But my work now has obviously been limited to using other people to physically make things for me. I’ve luckily been able to find people who can help me with that. A lot of it is the accumulation of knowing what can be done, and knowing the possibilities of the different techniques which can be used in metalwork. All my machines and tools that I had accumulated over a lifetime – and I had many tonnes of it, because I used to make everything myself – I gave to Uganda, where I found they were setting up a foundry.AM: The Ruwenzori Sculpture Foundation, you mean?BK: Yes. I knew that they could use my equipment better than anyone else, because I know what Rungwe Kingdon was attempting to do, repaying his childhood because he grew up there, so Uganda seemed to be the best place to send it to. Somewhere where it would really be of use and help to a collection of young sculptors, rather than breaking up my collection. I know it has a future there. I was told a story, for instance, of someone out there who was making a piercing saw out of the spokes of a bicycle wheel. I thought, ‘Well, that shows determination, to say the least.’AM: Could you tell me a bit more about the development of your most recent work?BK: Well, it started with a series of drawings and paintings I’ve been doing, so it evolved from these. My first thought was how to incorporate some of the ideas I’ve been using in two dimensions into the third, and these paintings are what I’ve come up with. And then scale came into it, and so I asked Steve Furlonger to come and see me, and I said I wanted him to make what is now the black sculpture because, I said, ‘This is exactly the sort of thing I’ve been searching for.’ I’m particularly indebted to my friend Barry Goillau of Benson-Sedgwick,

who has made a considerable number of pieces for me, and he’s also made quite a few other things, like William Pye’s beautiful fountains. We’ve worked together for many years, so I knew I had someone who could help me translate my work into reality.AM: When I was at your studio a few months ago, there was only the black sculpture you just mentioned, Dhoon. Since then, that idea has obviously progressed to these two much larger pieces, Centurion and Coral. Could you tell me a bit about where these works came from?BK: I can’t remember, really. Because I no longer have the ability to make sculpture myself, I worked out a way of making my ideas come into three dimensions by really using my imagination. I was working on the piece which is now made of black polyurethane, and I realised that I’d found what I thought was the perfect solution – just incorporating both two dimensions and three dimensions in a single piece, by using the space which the sculpture would take, and that it would affect anyone looking at it in the same way as I was imagining it myself. Of course, when you make a piece of sculpture like this, it comes as an accumulation of thousands of different thoughts on sculpture: sculpture in the past, and sculpture which I’m thinking about making in the future. I was particularly interested in the idea – because I am fairly obsessed with the place I came from, the Isle of Man, which is mountainous and by the sea – that it would be wonderful to make something which would work in that landscape, and also in the studio. In particular, I imagined a piece of sculpture landing in a place called Scarlett, which is where a volcano came up millennia ago and left great, flat plates of limestone down by the sea, and I can just imagine a piece of sculpture which would work extremely well there, because it would incorporate both the land and the sea and do something rather than just stand isolated.AM: I’m curious as well about the reflective spheres. What prompted you to add these elements?BK: It was always my intention to use the spheres with the simple forms and the space within, so I think they actually help to bring the whole thing to life in a very straightforward manner. I’m very interested in using them as part of the sculpture, while retaining their separate identity.AM: I’ve noticed, especially in some of your older works like Sloc and Falcone, many of the sculptures have two elements that seem to be caught in a

moment that’s as harmonious as it is tense. Where does that interest come from?BK: Well, I’ve always found in all the years I’ve made sculpture – I’ve been making sculpture now for half a century or so – each one brings on another set of possibilities. I always felt that the reality of the process which goes into making something needs to be shown in the sculpture itself. The sculptures basically came from the idea of hanging, pulling, twisting and manipulating the form. I used that sort of reality by simply handling bits of steel, bronze, whatever, and also learning how to use my increasing technical knowledge over the years to be able to make decisions which come from my understanding – I mean, I was a great hunter of scrapyards, where I found infinite possibilities amongst the bits of broken metal. Including, I might say, using explosives to actually cause forms to happen in an unexpected manner. I’ve had a lot of fun out of making things which surprise me.AM: Is it too soon to ask what you’ll be working on next?BK: Having an exhibition always has an element of finality about it. I find it’s a necessity for me to be able to make things, paint things, to create something, which would surprise and delight me. I will continue to work for as long as I live. -

-

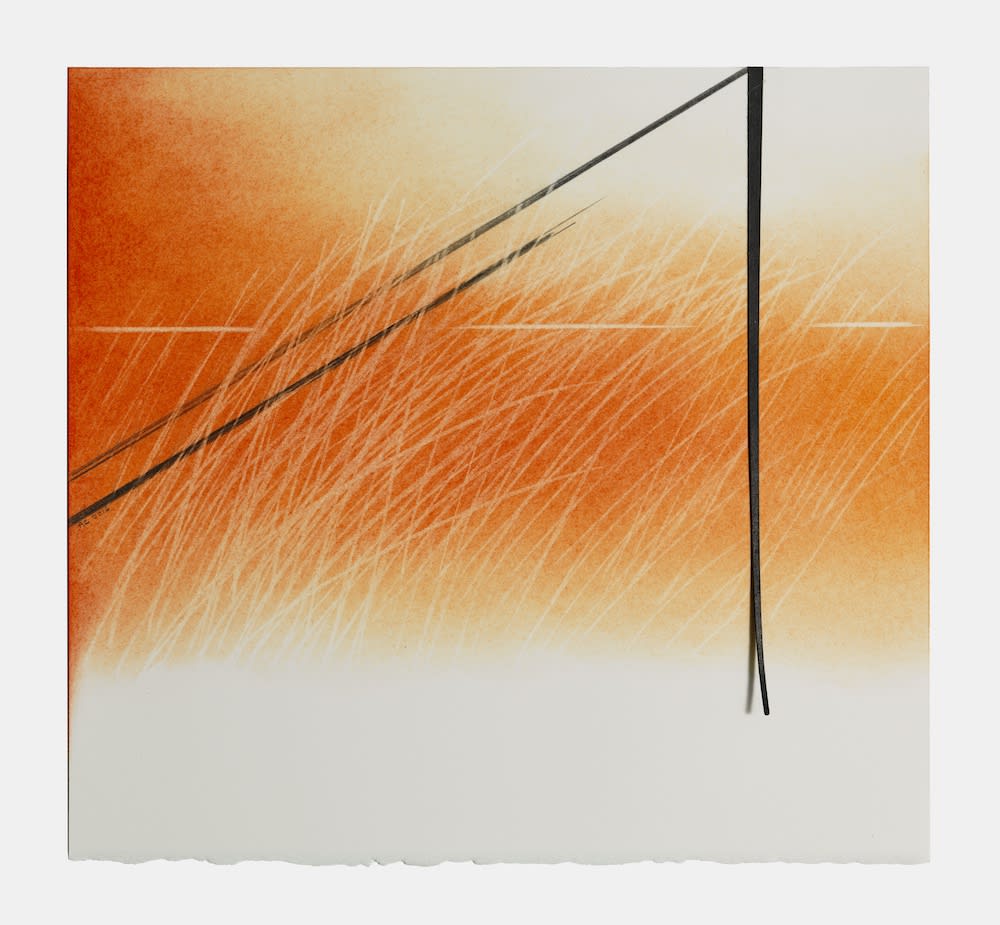

Ann Christopher, The Lines of Time 19

Ann Christopher, The Lines of Time 19 -

SCULPTORS' MATERIALS: STONE

Welcome to the #8 email in our series on Sculptors' Materials. This week we are looking at sculpting in stone.

The history of stone art takes us as far back as to the Palaeolithic era. People have carved into rock, painted on rocky cave walls, made figurines from stone, and toward the end of the Stone Age, constructed crude stone architecture.

Using rough stone and shaping it into a work of art has been practised by many ancient societies, and the durability of the material has allowed us, millions of years later, to take a peek into their unique culture and artistic practises.

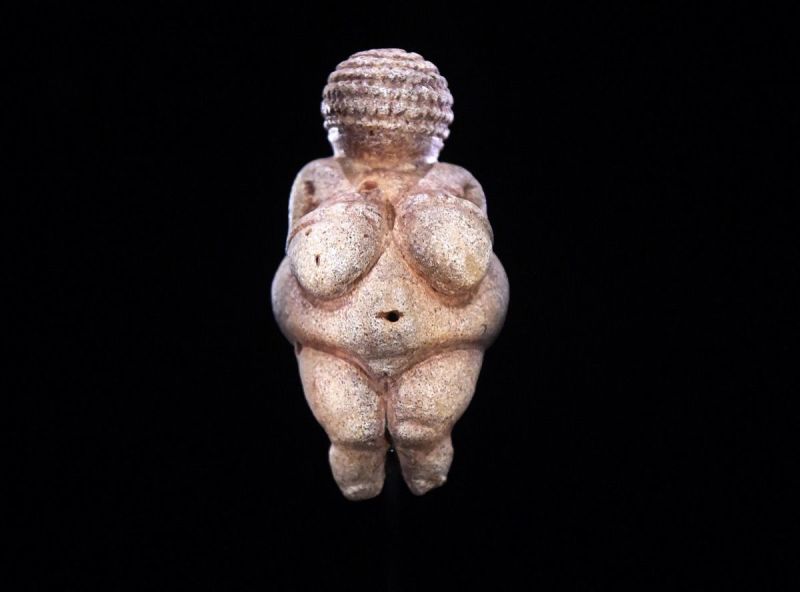

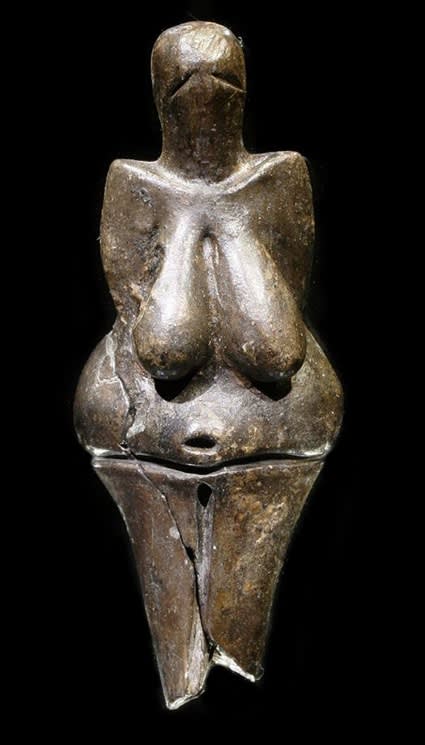

During the Stone Age, many used this material to make little figurative carvings, which began appearing across Europe from around 30,000 BCE. Since their creators were always on the move, the works were made on a small scale, in order for them to be easily transported. These richly coloured portable figurines often depicted humans gaining control over natural elements and animals – the latter were used predominantly for rituals that were carried out before a hunt. Fertility was another popular theme, as it represented prosperity and expansion of the tribe, which is why many Venus figurines were created at that time.

The Venus of Willendorf

c. 28,000 – 25,000 BCE, Oolitic Limestone, Approx 10 cm high, Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria

Some prehistoric Venus figurines may be as old as 800,000 years, and were often made from soft stone such as steatite, calcite or limestone. The Venus of Willendorf measures just over 10 cm and was discovered in Austria in 1908. Carved of limestone and originally tinted with red ochre, she is believed to have been made between 28,000 and 25,000 BCE, making her one of the world's oldest known works of art.

One of the most famous stone structures in England is the historical landmark Stonehenge, in Wiltshire. The monument consists of a ring of standing stones, each around 13 feet high, seven feet wide and weighing around 25 tons. It was built in several stages: the first monument was an early henge monument, built about 5,000 years ago, and the unique stone circle was erected in the late Neolithic period about 2500 BC. Two types of stone were used: enormous sarsen stones - a type of silcrete rock, which is found scattered naturally across southern England, and smaller ‘bluestones’ - these are of varied geology but all came from the Preseli Hills in south-west Wales, and they have a bluish tinge when freshly broken or wet.

One of the most famous stone structures in England is the historical landmark Stonehenge, in Wiltshire. The monument consists of a ring of standing stones, each around 13 feet high, seven feet wide and weighing around 25 tons. It was built in several stages: the first monument was an early henge monument, built about 5,000 years ago, and the unique stone circle was erected in the late Neolithic period about 2500 BC. Two types of stone were used: enormous sarsen stones - a type of silcrete rock, which is found scattered naturally across southern England, and smaller ‘bluestones’ - these are of varied geology but all came from the Preseli Hills in south-west Wales, and they have a bluish tinge when freshly broken or wet.

There are many theories about Stonehenge's original purpose – it may have been used as a meeting or celebration site, or even as an astronomical calendar.

The peak of stone sculpting occurred during the period of Romanesque art, followed by the Gothic architecture period that gave birth the greatest collection of three-dimensional religious stone pieces ever seen in the history of sculpture.

A popular choice for sculptors for many centuries, stone is valued for its natural elegance, sturdy nature, and versatility. As it is relatively easy to obtain and carve, it opens up a wide range of possibilities as it can be rough-hewn or delicately polished.

Different types of stone were used in different regions as sculptors used materials that were available nearby. A variety of limestone was employed all over Europe, and alabaster was popular in England, northern France, the Netherlands, Germany and Spain. Marble was commonly used in Italy, and exported to northern Europe from about 1550 onwards.

Michelangelo (1475 - 1564), David

1501–1504, Marble, 517 cm × 199 cm, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy

It was the famous Italian sculptor Michelangelo who saw the trapped sculpture he needed to release from a solid block of marble.

“I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.”How does the process work?

Whether working in igneous, mineral, sedimentary, metamorphic or semi-precious stones, the end result varies. The softer the stone, the easier it is to work with. While soapstone is the softest one and is commonly used by students of stone carving, the hardest and most durable is igneous rock, formed by the cooling of molten rock, and includes granite, diorite, and basalt. Stones such as alabaster, limestone, sandstone or marble occupy the middle part of the spectrum.

The tools used for stone-carving have largely remained unchanged since antiquity. A mason’s axe cuts out the basic form of the sculpture. This is further shaped or roughed out using picks, points and punches struck by a hammer or mallet. Different sizes of tool are used throughout the carving process to achieve different effects. Roughing-out tools leave deep, uneven grooves, whereas flat chisels achieve finer results and are used for finishing the surface of sandstone, limestone and marble. Further smoothing is achieved using rasps or rifflers (metal tools with rough surfaces), or minerals such as sand or emery (stone grit). Polishes can then be applied to fine-grained stone after it has been abraded. Marble and alabaster are polished with pumice, producing a smooth, translucent and reflective surface. They can also be left partially unpolished to create different textures.

Further smoothing is achieved using rasps or rifflers (metal tools with rough surfaces), or minerals such as sand or emery (stone grit). Polishes can then be applied to fine-grained stone after it has been abraded. Marble and alabaster are polished with pumice, producing a smooth, translucent and reflective surface. They can also be left partially unpolished to create different textures.

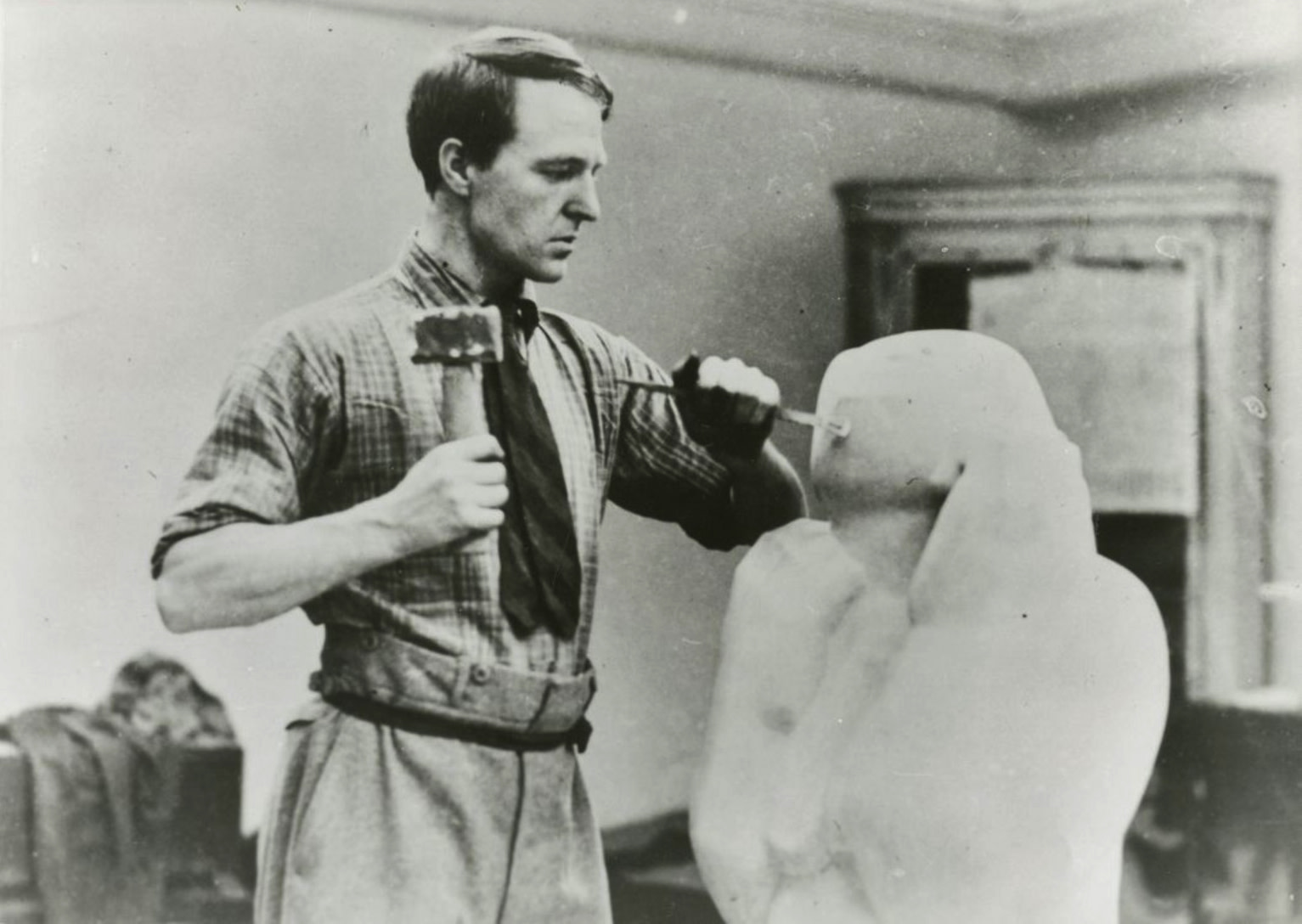

The 20th century completely reconsidered, redefined and reworked the concept of sculpture by introducing abstraction, and this brought new approaches to working in stone. Constantin Brancusi introduced the process of direct carving in 1906, where he would carve directly into the stone without carefully working out a preliminary model - usually made of plaster or modelling clay - beforehand. This practise was soon adopted by other established artists such as Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore (illustrated above). Despite similar tools being used to make stone sculpture today, we can also see a development in the making of stone work with the use of power tools and technology.

Despite similar tools being used to make stone sculpture today, we can also see a development in the making of stone work with the use of power tools and technology.

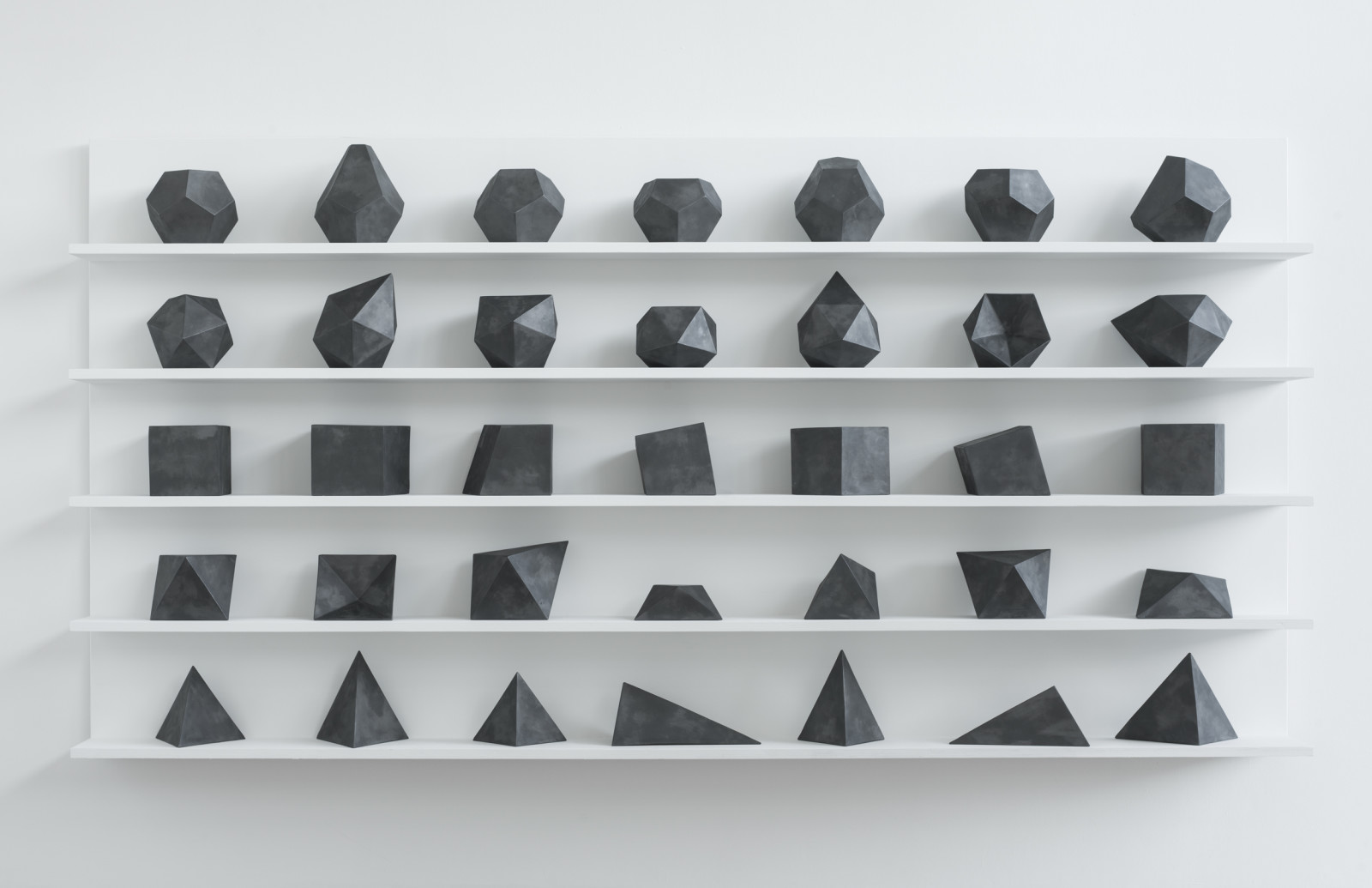

This beautiful marble sculpture was one of the highlights of ‘Divine Principles’, an exhibition by Zachary Eastwood-Bloom for the culmination of his year as Pangolin London's Sculptor in Residence in 2017. His work explores the intersection of the physical and immaterial, the historical and the cutting-edge, referencing classical imagery and adopting digital aesthetics to create his work. ‘Venus Celestis’ is a combination of the mythological figure, the personification of the planet and the surface of the planet itself. With this sculpture the philosophy of the ancient Greek is brought up to date by using exquisite CNC milling techniques.

Sculpture in stone gives a peculiar sense of grounding. Stone of all hues and textures have been carved into different shapes and forms over time. Chunks of dunite, marble and sodalite are re-imagined as figures, globes and other abstract forms in the sculptures below.

Peter Randall-Page

Geometry of Desire III

2015, Rosso Luana Marble

90 x 40 x 40 cm

Unique

Anthony Abrahams

Man with Raised Arm

Marble

Height: 135 cm

Unique

Steve Dilworth

Scored Stone

2016, Dunite

21 x 26 x 14 cm

Unique

Eilis O'Connell

Flung Blue

2019, Bolivian Sodalite

71 x 29 x 20 cm

Edition of 3A FEW FACTS ABOUT STONE1. As stone is so heavy, stability is important. Many free-standing marble figures in dynamic poses are portrayed with tree trunks or columns attached to the legs in order to provide a stable base.

2. Facebook censored the image of the 30,000 year-old Venus of Willendorf and deemed it as inappropriate and 'pornographic' content in 2018.

3. 90% of the carving for Mount Rushmore was done by dynamite. With 450,000 tons of granite to be removed, chisels were definitely not going to be enough. Borglum decided to try dynamite on October 25, 1927. With practice and precision, workers learned how to blast away the granite, getting within inches of what would be the sculptures' "skin."

4. Many famous buildings still standing today are made of marble including the Taj Mahal, The Washington Monument and The Parthenon.

5. One of the 10 most expensive sculptures sold at auction includes a 73 cm high stone sculpture Tête carved in 1911-12 by Amedeo Modigliani, which was sold at Christie’s in 2015 for $70.7 million (£44.2 mil). Today, most of Modigliani’s work can only be seen in museums, and very few pieces are still in private ownership. The sculpture shows traditional shapes reminiscent of the Italian Renaissance combined with the style of African masks and the moai of Easter Island. For a price list of stone sculptures, please click here.NEXT WEEK'S MATERIAL: ALUMINIUMImages: (From Top) Steve Dilworth, Lapwing; The Venus of Willendorf © Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria; Stonehenge, Wiltshire; Michelangelo, David; Henry Moore carving at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927 © The Tate; Zachary Eastwood-Bloom, Venus Celestis; Peter Randall-Page, Geometry of Desire; Anthony Abrahams, Man with Raised Arm; Steve Dilworth, Scored Stone; Eilis O'Connell, Flung Blue; Mount Rushmore with sculptures of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln (left to right) by Gutzon and Lincoln Borglum.

For a price list of stone sculptures, please click here.NEXT WEEK'S MATERIAL: ALUMINIUMImages: (From Top) Steve Dilworth, Lapwing; The Venus of Willendorf © Naturhistorisches Museum Wien, Austria; Stonehenge, Wiltshire; Michelangelo, David; Henry Moore carving at No.3 Grove Studios, Hammersmith 1927 © The Tate; Zachary Eastwood-Bloom, Venus Celestis; Peter Randall-Page, Geometry of Desire; Anthony Abrahams, Man with Raised Arm; Steve Dilworth, Scored Stone; Eilis O'Connell, Flung Blue; Mount Rushmore with sculptures of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln (left to right) by Gutzon and Lincoln Borglum. -

SCULPTORS' MATERIALS: IRONWelcome to #7 in our series of Sculptors' Materials. We hope you enjoy it!

SCULPTORS' MATERIALS: IRONWelcome to #7 in our series of Sculptors' Materials. We hope you enjoy it!

Iron is a material with a rich history and without its discovery the world as we know it would look vastly different.

Some of the earliest examples of iron date back to 3500 BC where beads of meteoric iron were worked into objects and weapons. Meteoric iron was the only naturally occurring source of iron readily available, as iron reacts readily with oxygen to form ‘iron ore’ and, as there is no oxygen in space, meteors deliver the material to earth in a way that allowed humans to use the material before having the tools themselves to extract iron from it’s ‘ore’. An ore is a naturally occurring material in which valuable minerals can be extracted.

One of the earliest examples of iron forging comes from a surviving gold handled dagger, found in the tomb of Egyptian Pharaoh; Tutankhamun. The dagger’s blade, made from iron, dates back to 1327 BC and by some miracle, still remains in near perfect condition today.

Iron is the 4th most common material found in the Earth’s crust, but as it reacts with oxygen an iron oxide forms which we see as rust. This is a common iron oxide and working to prevent rust is a constant struggle in structure maintenance.The single largest use of iron is to make steel, as iron alone is too soft for the strength required for structural value. The main difference between iron and steel is the amount of carbon each metal contains.

Anything with a carbon content of above 2% is cast iron. Anything higher makes it the material less ductile and more brittle. Cast iron is not suitable for structural use; its use in the mid 19th Century in some bridges led to their collapse. These were later replaced with wrought iron, which contains less than 0.8% of carbon, meaning it is more ductile, allowing it to bend under loads without breaking.

The tallest 'wrought' iron structure in the world is the Eiffel Tower and to prevent rust, every 7 years 60 tonnes of paint is applied to the tower, meaning it has changed colour over the years too. Did you know the tower was initially red? It has changed colour a few times until a special Eiffel Tower paint was established in 1968.

The world's first iron bridge open in Shropshire in 1781 over the River Severn, and was hailed as a pioneering advancement in British iron works, and design engineering. The bridge was so successful that it gave its name to the spectacular wooded valley which surrounds it, now recognised as the Iron Bridge Gorge World Heritage Site.

It was nearby, in the town of Coalbrookdale, that Abraham Darby pioneered the smelting of iron using coke, a process which is hailed as the catalyst to Britain's Industrial Revolution.Iron is also a material which has inspired generations of artists, either using the material itself within their craft or as an inspiration. Acclaimed painter Sir Joseph Wright of Derby's An Iron Forge, painted in 1772, is not only hailed as a perfect example of his light studies, but also as an important source which documents the realities of iron-founders and their process.

Sculptors too have enjoyed the ductile nature of iron. Pangolin London artist Geoffrey Clarke, after undertaking a welding course in 1951 at the British Oxygen Company, alongside fellow artist Lynn Chadwick and Reg Butler, used iron in vast quantities in his early works, producing his own visual language now iconic within Post-War British art.

Lynn Chadwick too used his skills learned at the course to create the inner frames of his now universally recognised watchers and beasts before they were cast in bronze.Artist Jeff Lowe (part of the group of sculptors known as the 'New Generation') too has experimented in cast iron sculptures.

A more 21st Century use of the material can be seen in Pangolin London's third sculptor in residence, Zachary Eastwood Bloom, who for his solo exhibition Divine Principles in 2017, cast the God of War, Mars, into iron - symbolic of not only the solar system's red planet but of the material used centuries before in weapon production which revolutionised the art of war itself.A FEW FACTS ABOUT IRON1. The element symbol for iron found on the periodic table is ‘Fe’, which comes from the Latin word for iron, "ferrum."

2. The Iron Pillar of Delhi, India, is a 1600 year old structure which stands 7.3 meters high. The pillar is said to possess special powers as the iron has never rusted!

3. The Eiffel Tower in Paris is the largest structure made from Wrought Iron in the world.

4. One of the world's most famous iron buildings, The Capitol, in Washington, DC has a dome made of cast iron.

5. Iron constitutes 5 percent by weight of the Earth's crust, and it is the fourth most abundant element after oxygen, silicon, and aluminium.

6. The word "wrought" is an archaic past participle of the verb "to work," and so "wrought iron" literally means "worked iron".For a price list of steel sculptures available, please click here.Images: Zachary Eastwood-Bloom, Orphan of Apollo/Mars, 2017, Iron; Tutankhamun Dagger. Image courtesy of The British Museum; Joesph Wright of Derby, An Iron Forge, 1772, Acrylic on Canvas. Image courtesy of Tate; Bruce Beasley, Aeolis 5, 2018, Cast Iron; Jeff Lowe, Taking Shape No.8, 2013, Cast Iron; Geoffrey Clarke, Effigy, 1951, Welded Iron, Unique. -

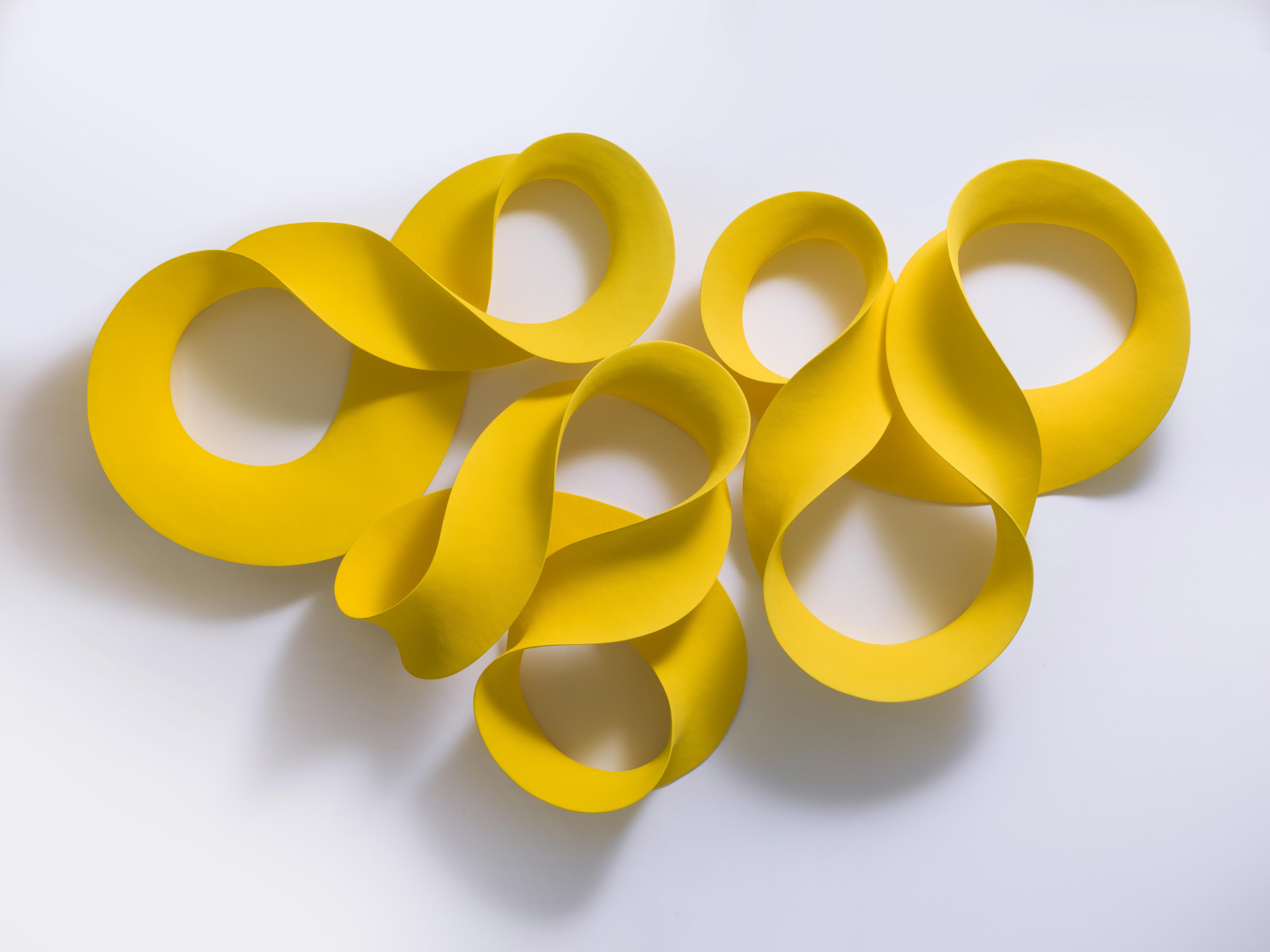

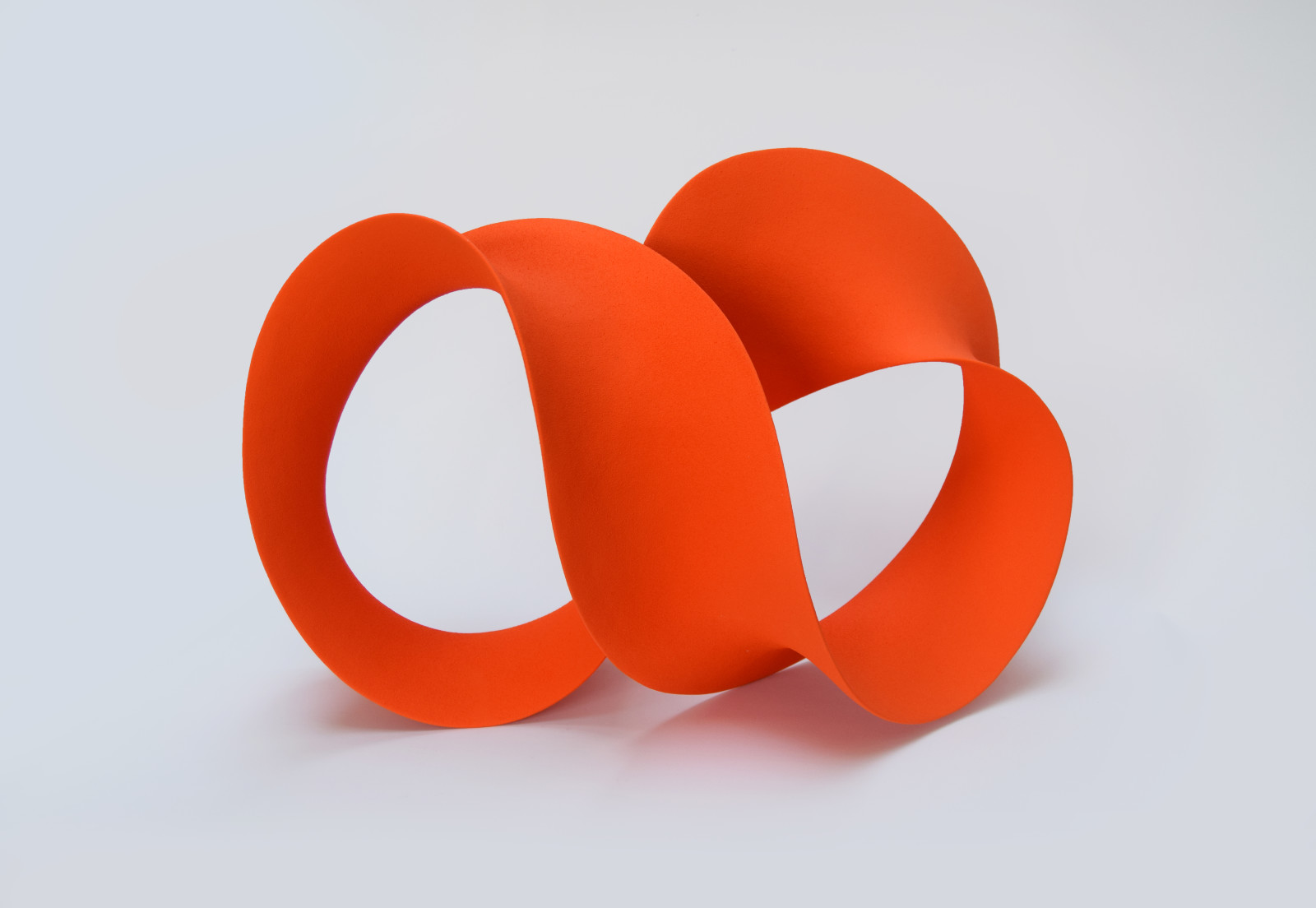

Merete Rasmussen, Ouroboros, 2019, Ceramic with coloured slip

SCULPTORS' MATERIALS: CLAY

Welcome to the #6 email in our series on Sculptors' Materials. If you would like to visit the gallery before Christmas, you still can! We are remaining open until the 23rd December by appointment. For now we are looking at the use of clay in sculpture over time.Clay is a fine-grained natural soil material containing minerals and a variable amount of water which gives it its plasticity. It is naturally developed after erosion and can be found near large lakes and marine deposits.

Clay is ideal for unlimited creativity thanks to its plasticity which helps the material to be malleable. It can be used for sculpture on any scale - from small figurines to large works. Any clay can be sculpted. Its colour changes depending on the oxides that it is composed of. If there is more iron, the clay will be red, if there is limestone in its composition then it will be white. With the addition of kaolinite you can get strong and translucent porcelain. In order to fire it, it needs a progressive heat from 25 to 1000 or 1200 degrees Celsius depending on the clay used. It then hardens and can no longer be changed. Ceramics is one of the world’s oldest crafts made by man using fire, before bronze and glass. Many sculptures were made of clay during the Palaeolithic period. Venus of Dolni Vestonice, now in the collections of the Moravian Museum in Brno, is the earliest clay piece that was found alongside other sculptures of animals and more than 2000 small balls of fired clay and dates back to 25 000 BCE. It measures 111 x 43 mm and was found amongst prehistoric ashes, broken in two. Researchers have found a child's fingerprints on it, and thought that he or she may have handled the sculpture before it was fired at a relatively low temperature (around 700C).

Ceramics is one of the world’s oldest crafts made by man using fire, before bronze and glass. Many sculptures were made of clay during the Palaeolithic period. Venus of Dolni Vestonice, now in the collections of the Moravian Museum in Brno, is the earliest clay piece that was found alongside other sculptures of animals and more than 2000 small balls of fired clay and dates back to 25 000 BCE. It measures 111 x 43 mm and was found amongst prehistoric ashes, broken in two. Researchers have found a child's fingerprints on it, and thought that he or she may have handled the sculpture before it was fired at a relatively low temperature (around 700C). Terracotta and clay were used from the Palaeolithic period to the Fall of the Roman Empire, and then we observe a decline in its artistic production and use during medieval times. It resurges during the Renaissance when clay models were made to then be cast into bronze. It was also a way for people to collect sculptures at a cheaper price as clay is a less expensive material than bronze. Ceramic art can be painted or enamelled to bring a similar finish to the sculpture.

Terracotta and clay were used from the Palaeolithic period to the Fall of the Roman Empire, and then we observe a decline in its artistic production and use during medieval times. It resurges during the Renaissance when clay models were made to then be cast into bronze. It was also a way for people to collect sculptures at a cheaper price as clay is a less expensive material than bronze. Ceramic art can be painted or enamelled to bring a similar finish to the sculpture.

The Chinese Terracotta Army Warriors, discovered in 1974 by farmers digging a water well at Mount Li, China is composed of more than 8000 warriors and horses in clay made between 246 and 208 BCE for the First Qin Emperor. More than 700 000 employees were hardly working on this project as the sculptures were supposed to serve the emperor in his afterlife.

Clay can also be used in architecture to decorate the exterior facades of the buildings. The Natural History Museum, The Victoria and Albert Museum and the Albert Hall in London are all covered with ceramic to give their facades more detail. Nowadays clay is becoming a more acceptable medium for contemporary sculpture and fine art, raising it from being considered only as a material for craft. Major international artists use this material to express their creativity.

Nowadays clay is becoming a more acceptable medium for contemporary sculpture and fine art, raising it from being considered only as a material for craft. Major international artists use this material to express their creativity.

Grayson Perry, the first ceramic artist to receive a Turner Prize in 2003, creates his vessels with complex surfaces using many techniques like glazing, incision, embossing and photographic transfers. Edmund de Waal went beyond the potential of ceramics mixing it with architecture, music, dance and poetry. Finally, Rebecca Warren uses the representation of female form in ceramic to express both tenderness and aggressiveness at the same time, always with a reference to other historical works and artists.

JON BUCK

PRESERVING VESSEL, 2018

FIRED CERAMIC

38 X 31 X 31 CM

UNIQUEPANGOLIN DESIGNS

STAG, 2019

GLAZED CERAMIC

89.5 X 53 X 35 CM

UNIQUEJASON WASON

BLACK AND GOLD JAR, 2018

CERAMIC

17 X 16 X 16 CM

UNIQUE Zachary Eastwood-Bloom, Sacred Geometry, 2017, Ceramic

Zachary Eastwood-Bloom, Sacred Geometry, 2017, Ceramic Merete Rasmussen, Fluid Form, 2020, Ceramic with coloured slipA FEW FACTS ABOUT CLAY:

Merete Rasmussen, Fluid Form, 2020, Ceramic with coloured slipA FEW FACTS ABOUT CLAY:

1 - The potter’s wheel was invented in Mesopotamia between 6000 and 4000 BCE facilitating the creation of uniformed bowls and vases.

2 - It is on a pottery that archaeologists have found the oldest writing in Ad Putea, Bulgaria, in a fort that used to be a Roman road station. The 7000 years old ceramics include two pictographic signs, a swastika and a group of other written signs.

3 - German potters are the first to produce stoneware in the 1400s. They then used finer clays and fired it at a higher temperature than earthenware. It was then more convenient and practical than earthenware as it was naturally non-porous.

4 - Picasso was a prolific artist in ceramic. In 1948, he learnt how to sculpt clay and stayed 7 years in Vallauris, a village in the South of France known for its artistic ceramic. There, he created more than 4000 original works, some of them were later edited from 25 to 500 copies.

5 - Today we can use clay (under its porcelain mix) to create hips, teeth or head skull prothesis - as ceramic is more stable and more tolerated than metal by the body.For a price list of works using clay please click here.

NEXT WEEK'S MATERIAL: IRON

To read last week's wood post, please visit our blog, where our Sculptors' Materials series will be available to view at any time.Images: (From Top), Merete Rasmussen Ouroboros; Venus of Dolni Vestonice, Moravian Museum in Brno, Photography: Petr Novák; Terracotta Army in Pit 1, Photography: Maros M r a z; Terracotta gargoyles on the Natural History Museum, London, Photography: the Natural History Museum ; Jon Buck, Preserving Vessel; Pangolin Designs, Stag; Jason Wason, Black and Gold Jar; Merete Rasmussen, Fluid Form. -

ARTIST IN FOCUS

ALMUTH TEBBENHOFF

Following from our Steel Newsletter, and having brand new work on display at Kings Place including a striking welded steel wall sculpture, we would like to present Almuth Tebbenhoff in this month's Artist in Focus.

Almuth Tebbenhoff was born in 1949 in Fürstenau, in northwestern Germany. She moved to England at the age of 18, where she studied ceramics at the Sir John Cass School of Art (1972-75) and in 1977 she studied drawing at the Royal College of Art with Eduardo Paolozzi. A few years later she established her Southfields studio in a former church hall, where she still lives and works today. Having grown up with a father who owned a welder, it wasn't long before Tebbenhoff explored this path and in 1986 she started a two-year course in metal fabrication at South Thames College, London.

"Sculpture is my language. First I worked with clay for over ten years, then I started using steel, a material that my father had used for his functional, agricultural inventions. Steel became my main material for the next 20 years and I invented my own particular technique using steel angle section. I wanted to achieve undulating lines without bending the steel - that felt too messy, so I made ‘pixillated’ curves by cutting randomly angled pieces and welding them together. I developed large open-sided containers from lines that moved and danced and to me looked humanised rather than industrial. These containers without walls made from steel angle section are very close to my heart. It’s the emptiness within them that has become such an important part of my life through silent meditation, which I have been practicing since 1983."

In the early 1990s, Tebbenhoff was invited by the Jodrell Bank Science Centre in Cheshire to mount a site-inspired installation. She showed a range of wall-mounted pieces, 'Petrified' in grey painted steel alongside their related, half-burnt welding templates. With their sharp geometries and fractal forms, they reveal Tebbenhoff’s pre-occupation at that time with illusory spatial planes and suggestions of other realms beyond the here and now.

Tebbenhoff's early steel pieces were mainly monochrome (referencing the sombre grey mood of a post-war Germany in the 1950s) abstract explorations of space and volume through geometric devices. From the early nineties, Almuth started moving towards a freer mode of expression, creating explosive forms in bright colours such as the striking work below, which is part of her Steel Garden series.In 2006, while on a residency in Pietrasanta, Italy, Tebbenhoff began to work with marble, and since then her practice has spanned a variety of materials.

"Steel had given me angular skeletal structures and the engineering side of my brain loved to solve geometric puzzles. The missing bit had been volume, which I got from marble. I now bounce between these two main materials, still making sculptures about light entering into a space/material and revealing nothing that you could put your finger on."Almuth Tebbenhoff now works mainly with steel, stone, bronze and clay aside from her drawings. Whether working on a miniature piece or on a monumental scale, Tebbenhoff always comes back to the same central themes of the universe and its vastness, eternity and the meaning of life.

“The infinity of cosmic space reduces us to mere atoms. (...) I mean my sculptures to be emblematic of a world built on foundations of love and compassion.”RECENT WORK

Almuth Tebbenhoff's most recent work meditates on notions of the self in relation to the world around us, and returns to organic colour and form. On display in the Ceramic Windows at Kings Place, ‘Who Will Buy my Dark Dark World’ consists of a group of sculptures that she started making during the autumn of 2019, as the world was heading towards the pandemic. Tebbenhoff's sculptures have the capacity to explore the most humble of subjects and familiar of forms while also communicating much grander concerns with creation, humanity and our relationship with nature.

READ an interview with the artist during lockdown.

BROWSE through a price list of Almuth's work.WATCH a short film about Almuth's ceramic installation.

WHERE CAN YOU SEE ALMUTH'S WORK?

Pangolin London

New Work, 2020

New ceramic work is installed in the windows by the main entrance to Kings Place. There are also further new works in the atrium. As well as her ceramic installation which is inspired by the pandemic, Almuth is also currently exploring steel circles, such as her new work 'Clef', illustrated above. The steel circles are a development from the doodles that started her Steel Garden series in the nineties - 'an expansive gesture that stretches the limits of my mind, yet it always pings back into the basic form.'

Click here for a list of works.St George's Hospital, London

Soft Pillar, 2004

'Soft Pillar' was commissioned after a competition for a site-specific work organised by the hospital, and is now located in the exterior garden atrium of the Atkinson Morley Wing. The work is a vertical rectangular open space-frame of a pillar, reflecting the brick pillars that surround it. Located in a side entrance of the A.M. Wing at St George's Hospital, another piece, Heavy Fields (1993), is mounted on the wall.David Wilson Library at Leicester University

Flying Colours, 2008

This piece comprises a series of interlaced open elements constructed from Almuth's signature welded steel facets. One inspiration for the piece was the sight of crumpled sheets of paper thrown up into the air.

“I wanted to catch the moment of pure frustration when the mind is locked in a dead end and then to set it free by an act of bravery – by throwing away what has been done to make way for fresh thoughts, for a new beginning. So there they are now floating freely through the foyer.”ALMUTH TEBBENHOFF WORKs AVAILABLE

-

OUTDOOR SCULPTURE

Gallery Director Polly Bielecka offers a few tips on placing sculpture outdoors - May 2020 Ann Christopher, The Edge of Light, 2002, Edition of 5.

Ann Christopher, The Edge of Light, 2002, Edition of 5.One of the unique pleasures of placing sculpture outside is seeing how the work looks each day in different light, seasons and weather conditions. If you are placing sculpture in a new garden design you'll need to think about how the garden might look like in ten years' time. Before making a purchase consider the practicalities - what is it made of, will it last, how is it constructed, does it require a plinth, how will it be secured and finally if you are concerned about investment research the artist's background.

-

Sudan, the last surviving male Northern White Rhino passed away on the 19th March 2018, leaving only two remaining female offspring. In the final days before he died Rungwe Kingdon of Pangolin Editions and photographer Steve Russell were asked by Ol-Pejeta Conservancy to travel to Kenya to scan this beautiful beast with the idea of making a life-size bronze and a maquette that could be sold to raise funds for rhino conservation and an inspirational project that could bring this species back from extinction.

-

TALKING PRINTS

1st April 2020 - Dr Judith LeGrove author of Geoffrey Clarke: A Sculptor's Prints talks about our exhibition 'Geoffrey Clarke:Intuitionism' Geoffrey Clarke, Adoration of Nature, 1951.

Geoffrey Clarke, Adoration of Nature, 1951.A talk, by way of a guided tour, written as an essay. A ridiculous idea? Unusual times call for creative measures, and this wonderful exhibition, marking 70 years since Geoffrey Clarke hit his stride as a printmaker, is one that should not be allowed to go unremarked.